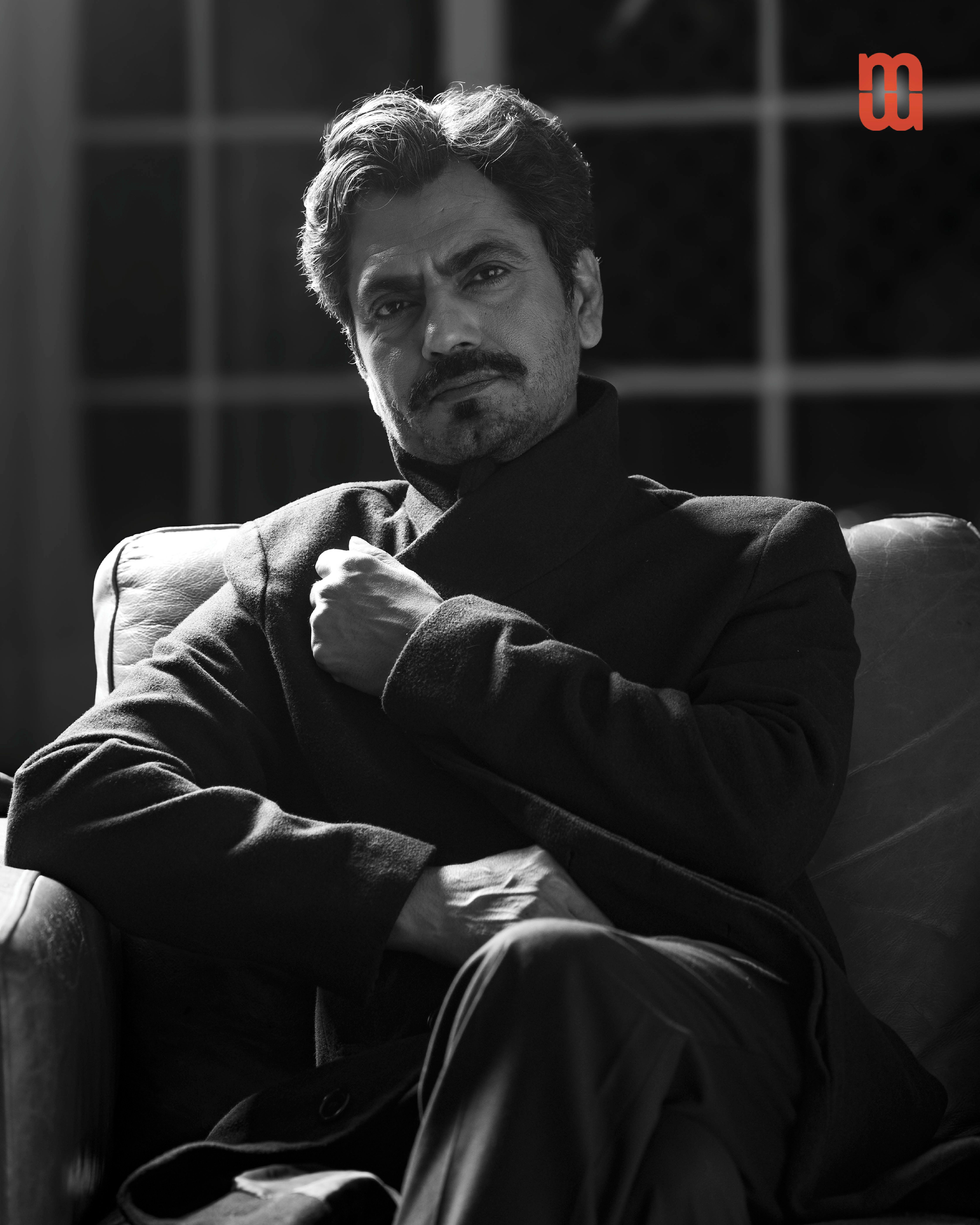

I first met Nawazuddin Siddiqui for a cover story in 2018. It was right before the release of Sacred Games—the Netflix series that would see him claim a ‘God’ status as Ganesh Gaitonde. The day had commenced with a 5-hour long outdoor shoot, involving multiple locations and four changes in Versova Koliwada steeped with a sharp stench of dried fish, under the scorching March sun. The wardrobe? Three-piece high-end designer suits, tuxedos, bow ties, et all. And the actor had stumped me with his fuss-free attitude and absolute surrender to the task at hand. He hardly spoke a word, calmly listening to the photographer’s instructions and executing those to the T, ensuring perfection in every frame. While the menacing mid-day sun was getting on the nerves of the crew, I couldn’t discern a rare smirk or a tell-tale sign of irritation on the Gangs of Wasseypur actor, who was already a star then with movies like Anwar Ka Ajab Kissa, Badlapur, Bajrangi Bhaijaan, Manjhi – The Mountain Man, Raman Raghav 2.0, Mom, and Raees bringing him critical acclaim as well as box office success. “Photo shoot bhi acting hi hai. I get so engrossed in the craft of acting that nothing else really matters to me,” he had said after wrapping up the shoot. According to him, it is the challenge of reaching the core of a character and making it as real as possible on screen that delights him, and not the money or fame. “Those are incidental,” the actor had claimed.

When we meet this time, the actor reiterates: “Mujhe star banna hi nehi thha.” Although the actor had moved to Mumbai after graduating from the National School of Drama (NSD) in 1999, it was not to become a ‘hero’. “Hume apni aukaat pata thi aur humne sheeshe mein apne aap ko dekha hua thha. Heroes back then didn’t look like me. I knew I didn’t fit the mould of the formulaic Bollywood Hero,” he guffaws. But he also adds that by the time he landed in Mumbai, Satya had already been released, and Manoj Bajpayee was quashing Bollywood stereotypes left, right and centre. “Manoj bhai and Irrfan bhai gave us a lot of confidence and hope.” Just as he didn't have delusions about his looks, he had absolute clarity about his capabilities as an actor. “I knew that I had trained myself so well that even if I get a 40-second role, I will be able to make an impact on the audience. I was doing theatre in Delhi but wasn’t earning enough to survive. I came to Mumbai thinking that I would earn some money—whatever is required for basic survival—by acting in television serials and picking up some bit roles in movies, and along with it continue to do theatre. Agar kuchh bhi nehi mila toh I would put together a theatre group and do street plays. I just wanted to keep acting and keep honing my craft,” says the actor, as we sit down for this interview under the watchful gaze of Anton Chekhov, William Shakespeare, and Konstantin Stanislavski’s life-size portraits. There are sweet mellow fragrances wafting from the flower bouquets that have arrived along with birthday wishes for the actor who has turned 51 just a day before. We are in the sprawling drawing room of his majestic bungalow named after his father, Nawab. Nestled in an upscale Versova neighbourhood, the quaint abode, hemmed by greenery, is largely designed by Siddiqui himself, drawing inspiration from his childhood home in Budhana and reflects the actor’s zamindari roots along with the aesthetics of a contemporary artiste. It is also a testimony to how far the chemistry graduate, whose initial professional stints included that of a security guard at a toy-making factory in Noida and a chemist at a petrochemical factory in Vadodara, has come by just finding his true calling and staying true to it.

But how did he initially sell the idea of moving to a new city to pursue art to his parents, especially since becoming a leading man in Bollywood was not even part of the dream at that point? I wonder. And I wonder out loud. “My parents were not educated. They had no clue what I was doing earlier or what I was planning to get into. They didn’t even know what theatre was, what NSD was. They were particular about just one thing: ke kuchh galat kaam mat karna...that I should not do anything unethical or illegal was their only concern. Thank god ke woh log anpad thhe otherwise they would have dictated me at every step, and I might not have become what I have become!” he laughs revealing that he got into acting accidentally. It was neither some dream he had nurtured since childhood, nor was it his one true love while growing up. The story is much less dramatic—he was bored of his job as a chemist but didn’t know what else he could do until one day while watching a play it struck him that acting is a profession where a person can never get bored—you are playing a different person every day.

But then, what happened to the initial plan of doing theatre in Mumbai? “I did one play after coming to Mumbai. Then I got busy with screen work, cinema mein maza aane laga. Now I am scared to perform in front of a live audience for two hours at a stretch—the body has lost the habit. But I am contemplating getting back; I want to do something with Manto,” he says. After his breakthrough performance as Faizal Khan in Gangs of Wasseypur, he had no dearth of opportunities to experiment and evolve as an actor. Anurag Kashyap’s two-part epic made Bollywood shift gears—the romantic escapism of chiffon saree and snow-capped mountains gave way to gritty and realistic narratives replete with raw human emotion. Siddiqui fit into this world perfectly. In the following decade, as content became the new ‘star’ of Bollywood, Siddiqui became its leading man. Between 2012 and 2018, he had a whopping seven movies screened at Cannes—one of the most prestigious international film festivals. Then in 2018 came Sacred Games and the Netflix series helmed by Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane, and Neeraj Ghaywan, made him an OTT star. Two years later he even picked up a Best Actor nomination at the International Emmy Awards for the Netflix original movie, Serious Man. But it is not that he has not attempted commercial Bollywood massy cinema. In fact, he has worked with all three Khans— he has done Kick and Bajrangi Bhaijaan with Salman, Talaash and Sarfarosh with Aamir, and Raees with Shah Rukh Khan. “I have nothing against such cinema; there is no harm in playing a commercial hero. As an actor one needs to be able to pull off every kind of character. The problem arises when one keeps doing just one kind of role. It is important for an actor to experiment.”

Talking about the exaggerated physical gestures and the loud and melodramatic dialogue delivery that are hallmarks of the ‘stars’ of such cinema, he points out that he sees no harm in it as mass cinema in India is performative and replete with dialoguebaazi. “The ‘loud acting’ is a part of mass entertainers. Even I love to watch that kind of dialoguebaazi on screen. For the audience, it is more entertaining to watch a scene replete with dramatic dialogues; realistic conversations can often become boring—it is more difficult to create an impactful scene in front of the camera where two people are just having a conversation. Also, since this kind of cinema needs to be larger than life, the pitch of acting needs to be a few notches higher than that of realistic cinema. More than nuanced and subtle acting, it is more about belting out a performance. But that is not to say that these kinds of movies don’t need good actors. For example, Amjad Khan’s performance in Sholay—those were simple lines which done by a lesser actor would not have had that impact. He made Gabbar iconic, he was a brilliant actor, he had even worked with Satyajit Ray—his range is enviable,” he says, pointing out that India has a tradition of performative acting. “It has its roots in our folk theatre and nautanki. Also, our initial movie actors often came from a theatre background—for example, Prithviraj Kapoor had a travelling theatre company. And in theatre, your performance, especially your voice, needs to be loud to reach the last row audience. So, their onscreen acting was also marked with exaggerated gestures and postures. It evolved but it took time. If you see actors like Dilip Kumar and Moti Lal, they brought a certain degree of realism to their acting. In fact, in their movies, you will often find that they are acting on a different pitch than all the other actors in the frame. That is not to say that it is only in Indian movies that you see such kind of acting. Even in Hollywood, it was the actors of silent cinema who were the first stars of the talkies; and acting in a silent movie demanded exaggerated physical performance and loud expressions,” he elaborates.

Siddiqui has in fact aced the dialoguebaazi in Sacred Games and Gangs of Wassaypur while keeping it realistic. In the Salman Khan-starrer Kick, Siddiqui created a character staying within the scope of massy Bollywood movies that is no less kick-ass than his turns in content-driven realistic cinema. And one of his favourite performances happens to be that in Heropanti 2 where his campy characterisation of the evil mastermind, Laila, to me seemed like a light-hearted hat-tip to Sadashiv Amrapurkar’s iconic character Maharani in Sadak. The actor says, “I wanted to bring in a slight feminine touch to make it extra edgy and evil. I tried a different walk, physicality, and dialogue delivery. But the movie didn’t work, and the performance didn’t get any recognition.” Be it commercial or arthouse, irrespective of the genre or the screentime, the chameleon actor has always shined as characters fitting into the space and scope of the movie with casual ease.

The NSD graduate credits his acting training for this. According to him, although acting can't be taught from scratch, formal training gives it a structure. “It provides you with the tools and techniques to grasp the spine of a character. It helps you in characterisation, it helps you build the backstory as well as getting the small nuances of the character right like weight-shifting, posture, et cetera. Then there are certain movies, for example, Badlapur, where you don’t prep at all but simply follow what the director’s instructions to the T—training helps you do the job well.” And what is his take on Method acting? “It is really not that complicated. Right off the bat, let’s be clear that as an actor, you never become a character; you project an impression of the character. Method acting teaches you the techniques through which you can prepare yourself to create that impression in the most authentic manner.”

But what about the current crop of young actors in Bollywood—their prep work is mostly confined to gyms and cosmetic clinics, instead of film school. “To be honest, the kind of cinema we make in Bollywood hardly requires any acting talent or training, yes there are a few exceptions. But we mostly work with a set formula; only the title of the movie changes. There are stock characters: there is a handsome and fair hero, who don't look Indian, he will romance a slim and pretty heroine and occasionally save her from an ugly-looking hero. There are song-and-dance sequences, action set pieces, etc. We have been peddling the same stuff for decades now. Even an actor starting off is familiar with these characters and can portray these fixed characters even in their sleep. You don’t need much acting skills to pull these off,” he scoffs. “Such movies are getting made because the audience is watching it; such actors are becoming stars because the audience is making the stars. A few rare occasions where you see people diss a movie or a performance for its quality, it is so because those are exceptionally bad.”

On the wall next to his International Emmy Awards nomination medal, hangs a certificate of merit for acting with the name Shora Siddiqui shining on it—hopefully a first of many, it is sign of the daughter following in her father’s footsteps. What is his take on that? “She recently attended an elaborate workshop at Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in London and followed it up with one in Mumbai. I am very categorical that if she wants to become an actor, she will have to train herself. I will help her in getting the right training, but she will have to get the movies on her own merit,” says Siddiqui, who is in no mood to offer his daughter the cushioning of an ’industry kid’. He also doesn’t believe that Shora has acting in her genes, and hence the training part is non-negotiable. “I am not quite sure if acting is something that is passed on through your genes—my father was a farmer; he had never done any acting,” he says. But he agrees that the environment she has grown up in might have an impact. “We watch movies together, there are discussions about cinema, she hears me analyse performances...I always tell her to watch difficult movies, movies that disturb her, that challenge her brain. Movies like Pulp Fiction, Memento, Irreversible, Ardh Satya...and Satyajit Ray’s entire filmography,” he says adding that he also wants her to watch specific performances like that of Anthony Hopkins in The Remains of the Day, Daniel Day-Lewis in Phantom Thread, Naseeruddin Shah in Sparsh, while preparing to be an actor. Although the actor dissuades his daughter from watching typical masala entertainers, he wants her to follow the works of Sri Devi, which he thinks is essential viewing for any actress prepping to work in commercial Hindi cinema.

“Today, the GenZs want everything simple and easy—I don’t want her to take that path. I keep telling her, jo filmein dekh ke mazaa aye, woh mat dekh. Our mind has a habit of going for easy things. But to progress, you need to give it difficult things. Sometimes it will be difficult for her to understand a movie, but once she finds a way in, it will be such a satisfying experience—that mazaa, once you taste it, stays with you,” he explains.

But what is her favourite performance of his? “Raman Raghav! 2.0! I had taken her to the premiere; she was around 5 years old then. I had to cover her eyes during the violent scenes. But a few days back she watched it again—this time the uncensored version—and loved my performance,” says the proud father, his eyes gleaming with joy. And any constructive criticism from the budding actor so far? “Papa aap dance mat karo! That's her only advice to me,” guffaws Siddiqui. And we can’t help but agree with the graceful 16-year-old stunner who is already grabbing eyeballs on social media.

Siddiqui is in no mood to dance around the trees either. He is busy earning praise for his recent release, Costao, a biopic of a customs officer from Goa in an attempt to bust a gold-smuggling racket got entangled in a murder trial in 1991. Essentially a story of an idealist going against a strongman, it reminded me of Shool, a movie that had Siddiqui in making brief appearance as a waiter—it was one of his very first screen outings. From that blink-and-miss part to playing the leading man, life has come a full circle for Siddiqui.

Over the years, his unwavering passion and dedication for cinema has continued to surprise me, often reminding me of Hendrik Höfgen, the protagonist of István Szabó’s Mephisto—while there the Faustian Bargain for Hendrik, who was a theatre actor, also involved fame and success, for Nawaz it is a single-minded pursuit of perfection in his art. While in the movie, Hendrik compromises his morals and values for fame, Nawaz claims that as an actor, one needs to be devoid of those to embody various characters. “As an actor I need to first believe in the character, otherwise how will I convince the audience? But when I am playing a character of a psycho killer as I did in Raman Raghav, my moral compass will act as an obstruction. In fact, while playing the character, I took off and spent about a week in a forest all alone trying to convince myself about the character. I am a selfish man. My loyalty is towards my art. If my ideology or moral values are getting in the way of that, toh phir mereko koi morality rakhne ki zarurat nehi hai. But I am not an animal, so I need to have humanity,” says the actor putting into perspective his brilliant performances in movies like Raman Raghav, where he plays an unhinged serial-killer Haraamkhor, where he plays a creepy sexual predator masquerading as a schoolteacher who preys on his students; or even Thackeray, where he essays the role of the titular founder and the firebrand leader of the Shiv Sena—a right-wing pro-Marathi, Hindu nationalist party. It was part ironical and part poetic justice, that a Muslim actor hailing from UP eventually played the part of a man whose party under him was known for its staunch Hindu fundamentalist views and hostility towards migrants from the North, particularly from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Facing backlash, the Siddiqui was then categorical: “I am an actor, I will do any role,” he had said in a media interview.

Such emptying of one’s soul to fill it with the soul of the character he is playing and surrendering oneself completely on the altar of art, is rarely seen in Indian cinema, especially among mainstream actors. What is more astonishing is that over the years he has not let materialistic temptations sway him from this path—it is almost a sage on the path of moksh.

In fact, while Siddiqui has kept evolving as an actor with each performance over the years, he remains almost the same person I had met the first time—humble, unpretentious, and unapologetically himself. His eyes still light up while talking about a performance, he still laughs at his own jokes mid-interview, he still has a soft corner for sharply tailored suits, and he still ends most of his sentences with ‘hai na’—the only change being that instead of rolling his cigarettes, he now calls for a pipe. He has remained the quintessential ‘outsider’ (think Meursault and not SSR), who even after spending 25 years in this industry, feels no obligation to fit in. “The industry is very small and everyone knows who is doing what. You don’t need to go to parties for that,” he says. It is the art and not the industry of cinema that interests him. “I want to totally focus on performance driven nuanced roles, more so today when there seems to be a dearth of those. There was a time when I was also taking up movies thinking about their commercial aspects—that it would be released in so many theatres, the box office, et cetera. But now I am focusing on movies jiska chalan na ho. I am getting such movies as well,” he says admitting that there is a marked deterioration of the quality of cinema in Bollywood post the lockdown.

On one hand, Bollywood, in a last-ditch attempt at resurrection, is trying to emulate pan-Indian cinema from the South, which is in turn mostly a rehash of regressive and tacky Bollywood cinema of the ’90s replete with casual sexism, toxic masculinity, and problematic portrayal of women. On the other hand, the OTTs, which had started off with the promise of becoming a platform for content-driven cinema, are today mostly reduced to churning out templatised content helmed by stars. Did Covid kill the content-driven cinema revolution that was heralded by GoW ? We ask Siddiqui, the poster boy and foot soldier of the movement. “There is currently no support system for content-driven good cinema. Unlike before, the OTTs are not willing to take risks anymore. Not all movies will go to Cannes, or get selected in international film festivals, so even if you make a good movie, what will you do with it?” rues the actor. But he is quick to point out that artistes can’t keep blaming the government, instead they must acknowledge their lack of effort and creativity. He strongly believes that crises can be a breeding ground for creativity. “I don’t believe in this narrative that we can't create good cinema because of the government and its policies—arre tum kya kar rahe ho, woh dekho! Creativity flourishes in times of crisis...look at Iranian cinema.”

Bollywood is today struggling with a creative bankruptcy—while there is a shortage of fresh new talents, the trailblazers, the outsiders who had pioneered the content-rich realistic cinema movement in Bollywood, seem to have either run out of steam or gotten disillusioned or opted for the comfort of cushy tentpole projects. For example, Dibakar Bannerjee’s last release was Love Sex Aur Dhokha 2 in 2024, Vishal Bhardwaj’s last release was Khufiya in 2023, Hansal Mehta’s last feature film, The Buckingham Murders, came in 2023, and of course Anurag Kashyap, the enfant terrible turned cop-out had his last Hindi release in 2023, the movie was Almost Pyaar with DJ Mohabbat —none of these had the creative sparkle or conviction of their previous works.

“Movies like Satya, and Gangs Of Wassaypur became landmark movies because of the team. It had talented writers, trained actors, and all were fueled with the same motivation—to make good cinema. But when such movies work at the box office, the motivation often changes. The same filmmakers, having gotten the required mileage, then opt for commercial movies with Bollywood stars. Aur muh ki kha ke aate hai. Anurag Kashyap is like a brother to me, I have immense respect for him, he is a genius. He knows his cinema very well and he has the pulse of his audience who are in remote villages, smaller towns, tier2 cities, and the bylanes of Banaras. When he makes a movie with a star who doesn't even know where Borivali is, how will he make him relate to his vision? And unless the actor understands the director’s vision, how will he perform? All the directors, who were at one point working with trained actors who could bring nuanced characterisations, gave in to the temptation of making big-budget commercial movies with stars. They could have made the same movies with those actors, but Bollywood doesn't make big budget movies with such actors. It is not that the audience doesn't want to watch these actors on the big screen, but the industry only keeps shoving the same few stars down their throat irrespective of their merit. Actors like me are struggling to get theatre screens—yehi struggle Irrfan ka thha, yehi struggle Manoj Bajpayee ka hai, aur yehi Naseer saab aur Om Puri saab ka raha hoga,” he says.

However, he is still optimistic that it is just a phase; part of a cycle. And filmmakers like Payal Kapadia give him hope. “If you are an actor or a filmmaker, the further you stay from Bollywood, the better. If Indian cinema has to find a world audience, it would be through these smaller, independent movies,” he had said in my interview last year, cautioning that the commercial trappings of the industry are notorious for throttling creativity. But Siddiqui is an actor who has managed to do just it. Unlike most of his comrades, he has stuck to his guns and refused to be a sellout. “It is not difficult to stick to your preference, even if it is different from what everyone around you is doing. You don't always need to fit in,” he says.

But can an actor really sustain in Bollywood focusing solely on creative satisfaction? “I am sustaining, I am doing fine; I am living a comfortable life. If money was the motivation, if financial success was the aim, toh phir mein sugar factory khol leta! We are farmers and we have enough land to grow sugarcane,” he says with a deadpan adding: “Aur kitna chahiye aadmi ko—waise toh hazaron khwaishen aisi ki har khwaish pe dam nikle...” he wraps up the interview with lines from his favourite poet, Mirza Ghalib.

Credits :

Editor-in-Chief: Radhakrishnan Nair

Writer: Ananya Ghosh

Photographs by: Neelutpal Das

Stylist: Yatin Gandhi

Hair & Makeup: Rajesh Nag

Artist Reputation Management: Spice