Indian festive fashion has a reputation for excess. Sequins heavy enough to bend a hanger, embroideries that could pass for body armour, lehengas designed less for movement and more for Instagram stills. Punit Balana has always been a quiet rebel against that tide. His tenth anniversary show at Rambagh Palace, Jaipur, was proof that shimmer and lightness don’t have to cancel each other out.

The evening was split into two acts. First came the opening of his flagship at Barwara House, a 3,000 sq. ft. retreat that reads less like a store and more like a love letter to Jaipur. Terracotta walls, arched doorways, bandhani-textured textiles, even curtains stitched with coins. It’s not retail therapy, it’s a geography lesson in Rajasthani craft.

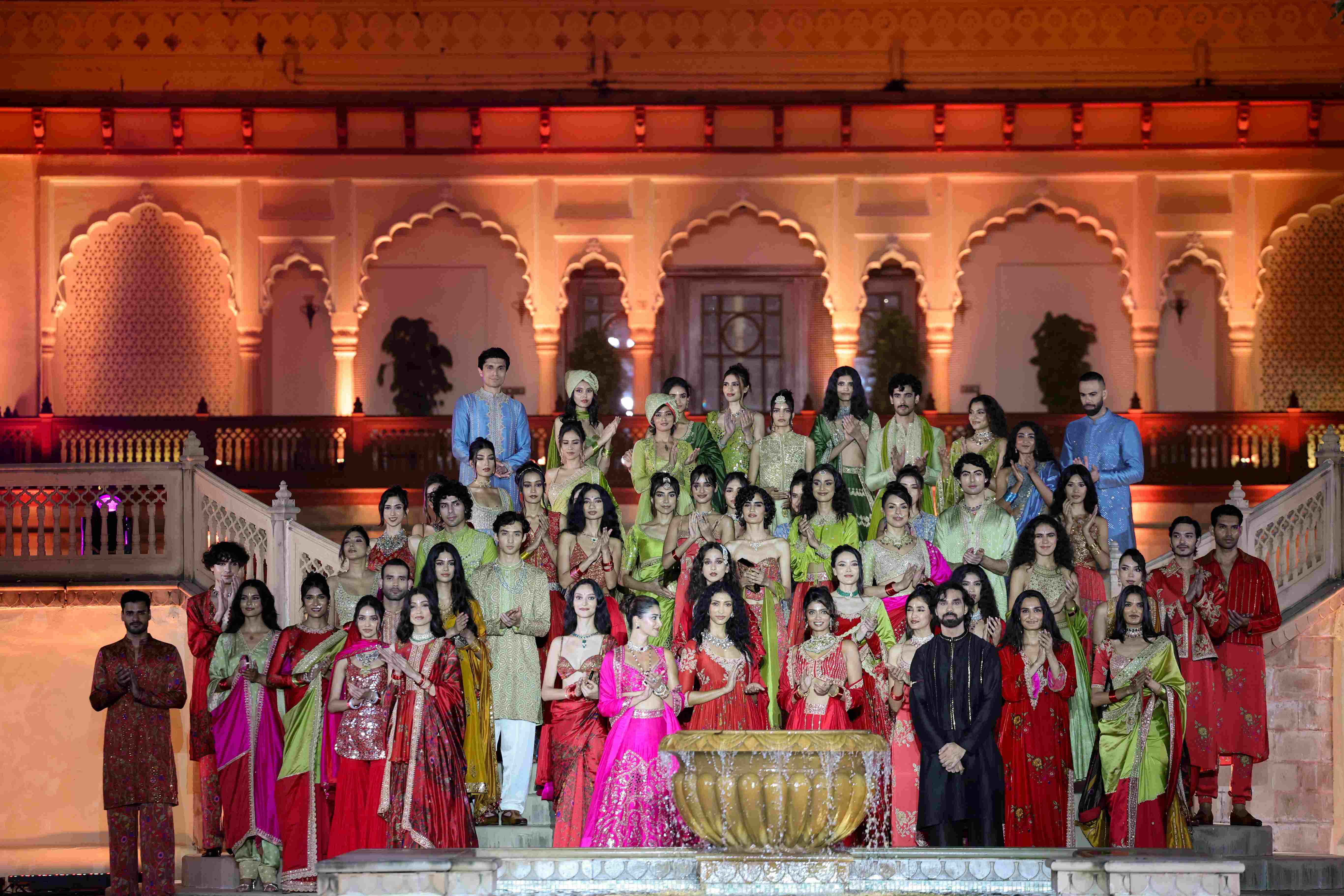

Then came Amer, his Festive 2025 collection, shown under the gilded arches of Rambagh Palace. Inspired by Amer Fort and its Sheesh Mahal, the line reached into Balana’s archive and pulled forward his greatest hits: cropped ghaghris, kedia sets, fuss-free ghagri maxis, flared lehengas, modern separates. The colours — Surkh Laal, Gulabi Gulal, Mustard, Dry Heena, and a new grey called Raakh — were familiar but made fresh, like old friends arriving in new clothes.

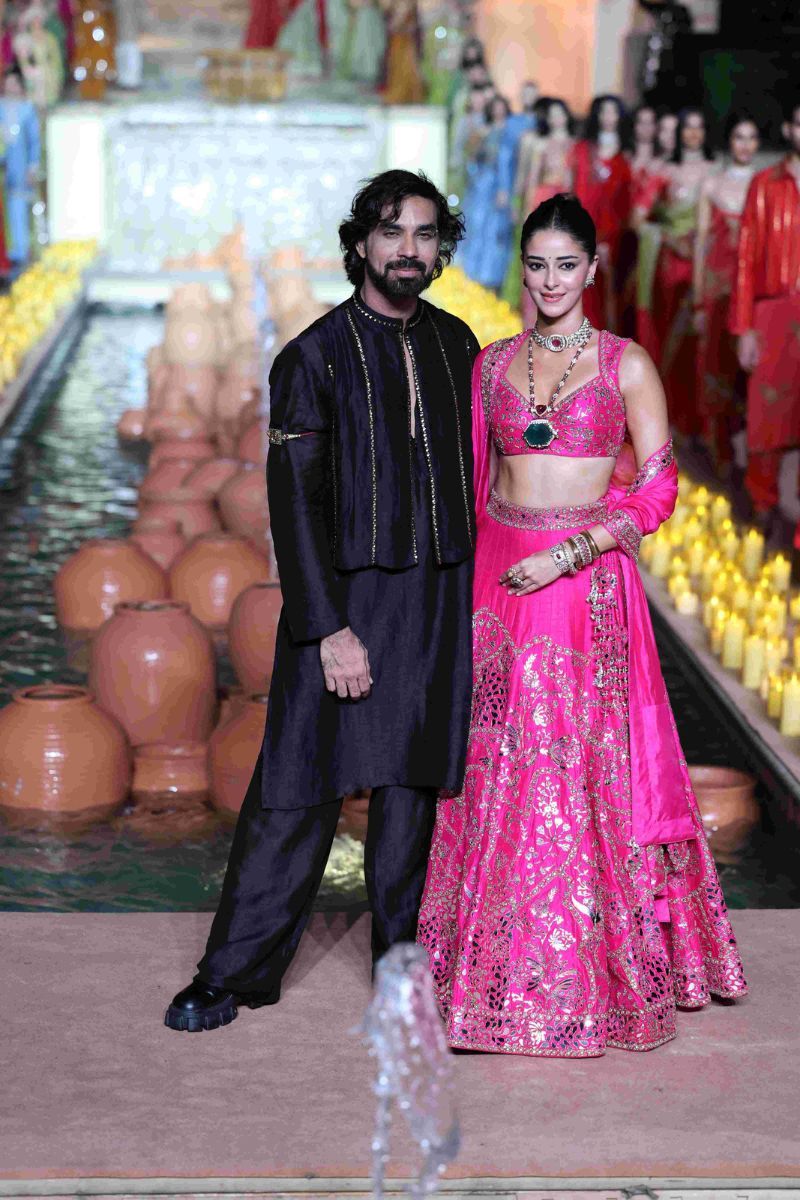

The craft was the real headline. Chaandi Tille Ka Kaam, his silver-sheet innovation born from the mirror inlays of old Jaipur havelis, lit up the runway. Instead of looking like replicas of palace walls, the embroidery felt feather-light, celebratory without tipping into costume. Ananya Panday, closing the show in a Gulabi Gulal lehenga cut with Chaandi Tille Ka Kaam, embodied the point: regal yet effortless, weightless but radiant.

The front row leaned into nostalgia. Bhumi Pednekar, Diana Penty — his first muse — Sunny Kaushal and Gurfateh Pirzada all turned up in Amer, a reminder that Balana’s clothes are not just for the runway but for the long road of memory.

What sets Balana apart is not just his techniques or colour palette. It is the refusal to overplay his hand. In an industry where heritage is often reduced to excess, he has spent a decade stripping things down — lighter ghaghris, cropped blouses, lehengas that move. He doesn’t costume women, he clothes them. That might sound simple, but in the world of Indian occasion wear, it is practically radical.

Jaipur was both muse and mirror here. The Rambagh Palace setting was opulent, yes, but the collection resisted the temptation to match grandeur with more grandeur. Instead, it let the details speak: the shimmer of silver sheets cut into embroidery, the pulse of old colours made new, the silhouettes that look at ease even in celebration.

Ten years in, Punit Balana isn’t chasing spectacle. He’s refining a language where craft is the vocabulary and Jaipur is the accent. At Rambagh Palace, he reminded everyone that festive fashion doesn’t have to creak under its own weight. It can float.