I AM NOT ASHAMED to say that I’ve nursed a fanboy crush on Abhay Deol since I watched him as the adorable crook in Oye Lucky Lucky Oye. There’s something about the guy’s natural affability that makes you always want to root for him. His filmography is any actor’s envy, with intelligent, niche films like Manorama Six Feet Under and Road, Movie (both cult DVD hits), mainstream successes like Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara and bold experiments like Shanghai, Ek Chaalis Ki Last Local and his tour de force — Dev D — which made him the go-to guy for anything edgy and cerebral. But then, after the debacle that was One By Two, he disappeared. I am literally seeing Deol after two years, because he does not attend parties and functions, nor does he do brand endorsements. ‘

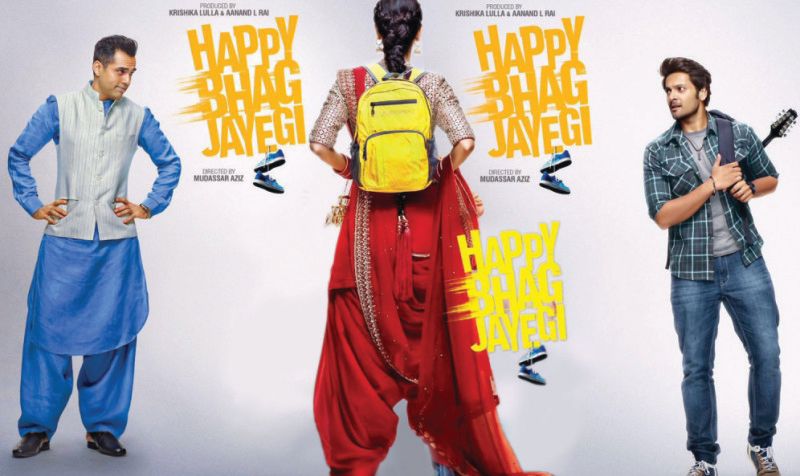

He is lankier, with a week-old scruff and a loud, boyish laugh that makes you laugh along with him, even when the joke is not that funny. Deol is one of the very few mainstream actors of our generation who did not run around trees or get into CGI-aided fight sequences, ripping shirts and spitting blood. He struck a fine balance between the commercial (but not necessarily massy) and the intelligent, and became a favourite with the urban crowd. He is posh, no-nonsense and quite the regular Joe — you can connect with him as easily as you connect with your best bud, which is exactly what makes Abhay Deol work. Even those who enjoy massy potboilers don’t necessarily connect with the stars on screen, because the films are usually narcissistic homages to feed the stars’ already bursting-at-its-seams ego. Even as the lead of a film, Abhay Deol has never played the “hero”. Even as a hardened thief or drug-addled spoilt brat, his performances have been natural, logical and empathetic. When I meet him, I sense a lack of worldliness and greed — he is not trying hard to be anything, or impress anyone. The man, quite surprisingly, seems content. Does he know what the future holds in his second innings? Maybe not. But he sure as hell has the confidence to figure his way out again — and on his own terms. I almost want to call Happy Bhag Jayegi his “comeback” (the tabloids’ favourite term for actresses who get back to work after marriage and children), but then again, why can’t film stars take holidays?

Welcome back. What have you been up to?

Thank you so much. I have been travelling a lot. I suppose in a way it has been great, because when you take a gap year, you get to revisit and reinvent. It has definitely been eventful on a personal front. I travelled a lot. I spent time with my family in the US. I was just living my life. When you are in a creative field, that helps. Whenever I do films back to back, it gets very difficult because you go back to stock emotions. That happens because you haven’t let life happen, you have not been sad in another way.

How has the industry reacted to you? You are coming back after two years.

I have always kept myself away from the industry. In the beginning, it was not a very open place, and they knew me from my family and I was not doing what my family was doing. And they judge you for what your image is. So, initially, they didn’t quite care about who I was. Then when my films started getting critical and commercial success, they took notice. And because I did not take a mainstream route, the same guys who didn’t think I would be a success, now started to approach me with mainstream offers and I turned them down. I was like, the only reason you are coming to me now is because the non-mainstream work had been successful. Then why should I do mainstream work? That translated as arrogant and egotistical, but my experience had been that. Logic told me this. So, the industry only responds to the way you are. I realise the way the industry was perceiving me. My director, Mudassar [Aziz] of Happy Bhag Jayegi keeps saying that I am always misunderstood. I am upfront, which I think is a polite thing to do, which a lot of people don’t like. But I don’t blame the industry for being resistant to me, because when I was doing experimental work, no one else was. So, I can understand why they did not want to take a chance on me.

But do you think it would be easier for you to do the kind of films you did, today?

But do you think it would be easier for you to do the kind of films you did, today?

I don’t know. No one is making a Dev D, Manorama [Six Feet Under] or an Ek Chaalis [Ki Last Local] even today. I feel it was easier for me to do those films back then. Even for Navdeep [Singh, director of Manorama Six Feet Under], it took seven years to make a NH 10, which is a revenge drama and is as commercial as it gets. A Manorama is so much more layered and subtle than a NH 10, which is in your face. If we were doing better, directors like him would be far busier.

So what kind of films are you looking at now?

The same. Happy Bhag Jayegi is kind of in the same space. While it might have the packaging of a mainstream film, it does not go where you would expect it to, and that is something I love about the film. But yes, if given an opportunity, I would love to do a Manorama or a Shanghai again. I have one project I really like which has come my way, and I hope it gets made.

Do you still feel like a misfit in this industry?

Yes, I suppose so. It has taken me longer to understand the things which most newcomers today have a clear picture of even before they come in — and I was born into the industry, you know, which makes this even more ironic. What I saw as a kid growing up were the things I wanted to avoid. And I have. But those are the very things that people want. So the things I wanted to avoid are the things you usually want if you want success.

Why hasn’t theatre ever been on the radar for you?

I haven’t done theatre. In college, yes, and a couple of workshops afterwards, but nothing more than that. I have worked on the craft from a theatrical approach, but theatre and film are different. And theatre is hard work and I am a lazy bastard (laughs). And it is a longer commitment too.

What’s the last film you saw and loved?

I have hardly been watching films. I don’t think I have watched a film in the last two years, and if I have, I have forgotten. I do watch stuff on long flights, but that’s when you catch the rom-coms and animations. You want to save the good films for the big screen, and I never end up watching them.

What are you reading these days?

This book called Sialkot Saga that I picked up recently.

Does stress work as a form of motivation for you?

I don’t like stress. And I don’t think there is a thing called positive stress, because stress by its very nature is negative. I can understand why a little bit of nervousness and anxiety might be good, those are states of mind. But stress is the materialisation of anxiety. See, I like what I do, so I don’t need motivation because it is already there. It is like asking what makes you eat. When you are hungry, you eat. It is a part of your natural process. Making movies is a part of my natural process.

Dev D

So, in these last two years, you haven’t felt motivated enough?

I wasn’t — true that. And I think spending the two years outside work gave me the motivation again. It’s been a while since I have done a film, so now this one will release and we’ll see how it goes.

Does that matter?

For the industry, yes. It matters to me because it matters to others who will invest in me. It doesn’t matter personally. I have done my job. It is not just making a movie that makes it a success. So, for example, Manorama flopped when it came out. It made it more difficult for me to get the next film. But it became a cult hit on DVDs. The audience needs to understand that when they don’t invest in these films, what it is telling the industry is that these films are not liked by the audience. They don’t give a shit about DVD sales.

But you’re hungry again?

Yeah (laughs).