When Sotheby’s listed the Piprahwa jewels for auction in Hong Kong this May, it was billed as the sale of a lifetime: nearly 1,800 pearls, rubies, sapphires, and gold sheets believed to have been buried alongside the Buddha himself. What followed was a global uproar. Buddhist leaders called it sacrilege, Delhi threatened legal action, and scholars questioned whether sacred relics could ever be treated as commodities. After two months of tense back-channel negotiations, the auction house has backed off. The Mumbai-based Godrej Industries Group has acquired the jewels and will return them to India for permanent public display, closing a 127-year chapter that began in a stupa near the Buddha’s birthplace.

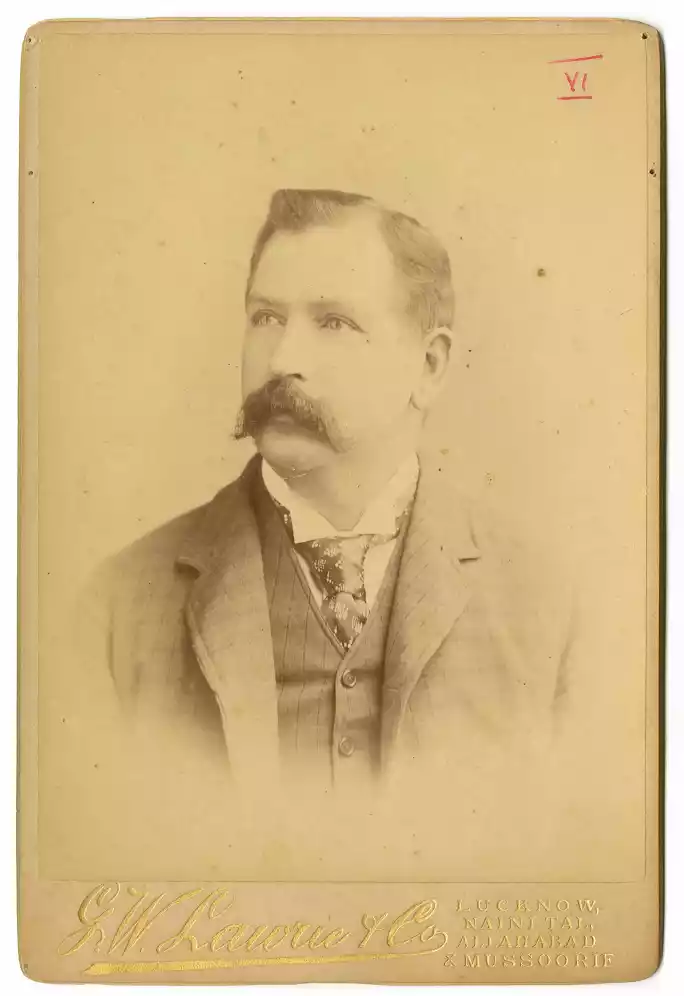

The jewels were first unearthed in 1898 by William Claxton Peppé, an English estate manager who excavated a stupa in Piprahwa during the famine of 1897. Inside, he found bone fragments marked by an inscription naming the Buddha and an extraordinary cache of gems believed to have been offered by his own Sakya clan. Most of the relics were passed to the colonial government, the bones to the King of Siam, and the rest to museums. But a small portion of “duplicates,” as they were called, remained with the Peppé family. For over a century, these stayed hidden in a private collection, mentioned in old newspaper clippings and family letters but rarely seen. Chris Peppé, William’s great-grandson, recalls first spotting them as a child in a glass case at a relative’s house—at the time just “little gems with long stories about India” he didn’t yet understand.

That inheritance became a quiet burden. Over four generations, the Peppés debated what to do with a set of jewels tied not only to archaeology but to faith, history, and colonial power dynamics. In recent years, they made efforts to put them on public display: from Zurich to New York’s Met, Singapore to Seoul. A dedicated website published William’s handwritten notes and diagrams from the excavation, his letters revealing both Victorian prejudice and unexpected empathy—a man engineering ramps and pulleys to give tenant farmers famine work, while digging up the ashes of one of the world’s great spiritual figures. Still, these objects sat uneasily in private hands, waiting for resolution.

That came only when Sotheby’s announced the Hong Kong auction. The listing sparked outrage: Buddhist communities saw an affront to shared heritage, historians questioned the right to sell, and Delhi intervened. Chris Peppé defended the auction as a transparent way to transfer ownership, saying few Buddhists considered the gems corporeal relics. But global opinion settled on one point: these weren’t just antiquities. They were symbols of devotion buried two millennia ago and tied to human remains, far removed from the market logic of art sales.

This week’s deal—brokered between the family, Sotheby’s, the Indian government, and Godrej—finally gives them a permanent home in India. It’s an ending that feels closer to how the story should have read all along: sacred offerings taken from the ground in 1898, travelling through colonial hands and private vaults, now returning to public guardianship, 127 years late.