Last week, Mumbai’s horological inner circle gathered to celebrate a milestone years in the making — the launch of A Sense of Time, watchmaking and luxury expert Anita Khatri’s first-ever coffee table book, unveiled by actor and watch collector Shilpa Shetty. It was an evening marked by warmth rather than spectacle, where collectors, brand partners, and industry friends came together to honour one woman’s thirty-year journey through the world of watches.

Shilpa, speaking at the unveiling, reflected on why the project resonated with her. “Time has always fascinated me, not just as something we measure but as something we live through, moment by moment,” she said. “What Anita has created is remarkable — she’s turned decades of passion and knowledge into something tangible and beautiful. It reminds us that watches are not only about luxury or precision but about emotion, memory, and even the future.”

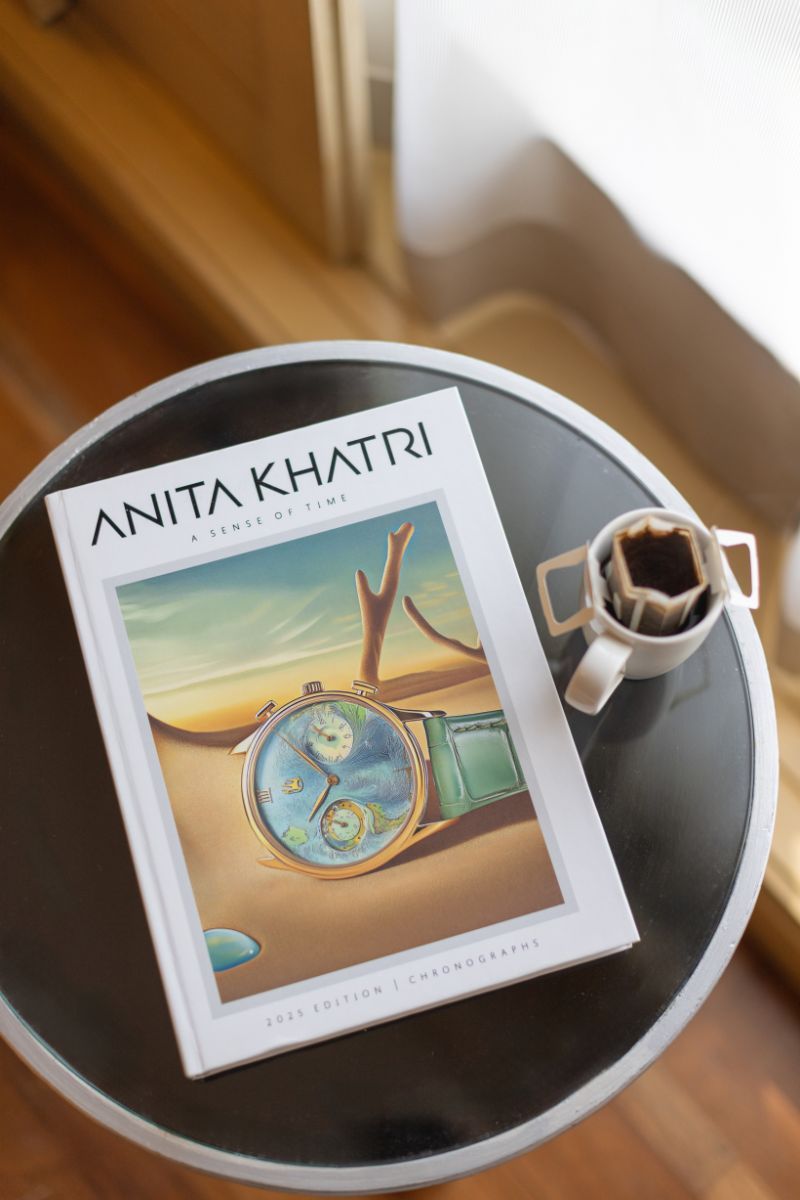

For Anita, A Sense of Time is the culmination of three decades spent writing, curating, and teaching horology in India. “Each page,” she said, “captures the essence of what makes watchmaking so captivating — design, craftsmanship, and the human connection we build with time itself.” Limited to 1,000 numbered copies and priced at ₹18,000, the book marks the first in an annual series, with future editions each exploring a new chapter in the story of fine watchmaking.

The inaugural edition is devoted entirely to the chronograph — the most celebrated of watch complications. It begins with an evocative foreword tracing humanity’s obsession with precision, before unfolding into essays that mix archival storytelling with accessible technical insight. From Louis Moinet’s 1816 Compteur de Tierces to Longines’ 13ZN and Breitling’s era of pushers, the book balances the mechanical with the poetic, never letting you forget why these watches matter beyond their cases and calibres. Each section is richly photographed, interspersed with reflections from the likes of Benoît de Clerck of Zenith and Laurent Lecamp of Montblanc, giving the volume an international yet deeply personal character.

Visually, A Sense of Time reads like an exhibition in print. Its pages shift between full-bleed imagery, archival sketches, and crisp technical spreads that feel deliberately slow, almost meditative — an antidote to the pace of digital media. It’s designed to be read, revisited, and eventually handed down, just like the watches it celebrates.

For Mumbai’s collectors, Friday night wasn’t just about a launch. It was about a landmark moment in Indian watch culture — the point at which a homegrown voice took its place in the global conversation of horology. Here's an excerpt from the book's opening chapters:

Excerpt: Birth of the Chronograph

(From A Sense of Time: The Chronograph Edition*, 2025)*

Timekeeping is often mistaken for certainty. Its numbers appear clean, precise, objective — as if history moves in straight lines and neat intervals. But scratch beneath the surface of horological history and you’ll find it riddled with disputes, disappearances, and devices that were far ahead of their time, or quietly forgotten by it.

Few complications embody this tension more fully than the chronograph.

By definition, it is a machine that measures elapsed time; a stopwatch embedded within a watch. Simple enough. But try to pinpoint its origin, and the waters quickly grow murky. One version begins in the 1820s, at the local races. Another starts five years earlier, inside a Parisian observatory. One invention was relatively crude but popular. The other, precise but buried. Both were born of need, but only one survived long enough to shape memory.

The deeper you dig, the more you realise this is not just a tale of mechanisms and patents. It’s a debate about what counts. Can a tool be called the “first chronograph” if it wasn’t commercialised, named, or even remembered? Or does influence matter more than ingenuity?

The story that follows is part archival mystery, part philosophical inquiry — a complication in its own right. It begins in an age of sharpened curiosity, when scientists and statesmen alike demanded new ways of capturing time in motion. And it leads, eventually, to one of watchmaking’s most enduring paradoxes: that a complication designed to measure things with precision should have such an imprecise origin.

An illustration from Samuel Watson’s Physician’s Pulse Watch (1695), created for English physician John Floyer. Among the first watches built for scientific use, it let doctors measure a patient’s pulse accurately — up to 120 beats per minute — using a hand calibrated to fifths of a second. By turning a medical need into a timing instrument, Watson and Floyer unknowingly laid the groundwork for the modern chronograph.

By the early 1800s, the world was no longer content to simply tell the time. The age of precision had begun to take hold — in science, in medicine, in the shifting rhythm of modern life. With it came a new desire: to capture time in motion. To isolate seconds from the stream. To record them.

Nowhere was this more urgent than in the observatory. Astronomy, once governed by the slow churn of seasons, had narrowed its focus to fractions of a second. Timing the exact moment a star crossed the eyepiece, aligning a telescope to a planetary transit, calibrating an astronomical clock — all required timing tools beyond the scope of standard watches. The transit of Venus, for instance, could take just six minutes, and the critical midpoint passed in less than five seconds. Miss it, and you’d wait over a century for another chance.

Physicians, too, were reaching for something more precise. In an era when diagnostics were turning empirical, the ability to measure a pulse over ten or fifteen seconds could offer critical insight. But measuring those seconds with a standard watch demanded a steady eye and mental arithmetic, which was a fragile system in moments that required certainty. Lives could hinge on seconds, but those seconds were being guessed at.

There were attempts to bridge the gap. In 1695, English horologist Samuel Watson built a device for King Charles II’s physician — a sort of proto-stopwatch designed to calculate heart rates. It could be started and stopped on command, but it lacked a return-to-zero mechanism. That made it useful, but not repeatable. In the eighteenth century, George Graham’s deadbeat escapement refined the ticking of seconds into clean, individual pulses. Jean-Moïse Pouzait, in Geneva, went further still, designing a pocket watch with an independent seconds hand that could be paused. But once again, there was no reset. Each reading existed in isolation, with no reliable way to compare one to the next.

These were not failures. They were stepping stones — attempts to tame time in shorter doses, to treat seconds not as part of a continuum, but as discrete intervals worth measuring.

And elsewhere, pressure was building. Engineers timing steam releases. Chemists tracking reactions. Artillerymen marking fuse delays. The appetite for measured time had outpaced the tools available.

Still, the instruments remained stubbornly incomplete. You could start a count. You could stop one. But returning to zero — cleanly, precisely, and reliably — was a frontier no one had yet crossed.

In the long arc of watchmaking history, Louis Moinet is a figure often glimpsed from the corner of the eye. A contemporary of Breguet and an occasional collaborator, he was born in 1768 in the French town of Bourges and educated not just in mechanics but in the arts. Before entering horology, he trained as a painter and sculptor in Rome, Florence, and Paris, lending him a classical foundation that shaped his workbench as much as his worldview.

Moinet was a craftsman of rare discipline, with little interest in commercial flair. He preferred to work alone, and when he did accept commissions, they were often scientific in nature: clocks for astronomers, regulators for royal observatories, precision instruments for clients who prized accuracy over decoration. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, he had become known among Europe’s intellectual class as a watchmaker fluent in the language of stars.

It was this affinity — the shared vocabulary of time and astronomy — that led Moinet to a particular problem. At the observatory, he struggled to time celestial transits with the tools available. A planet crossing a telescope’s field of view could take a few short seconds. Observing it was simple. Recording the precise duration — again and again, without error — was not. No standard watch could do it. Even the finest regulators of the day lacked the ability to start on command, stop at will, and return to zero. That gap between observation and measurement became Moinet’s challenge.

To order a copy of A Sense Of Time, please send a request on @anitakhatriasenseoftime.