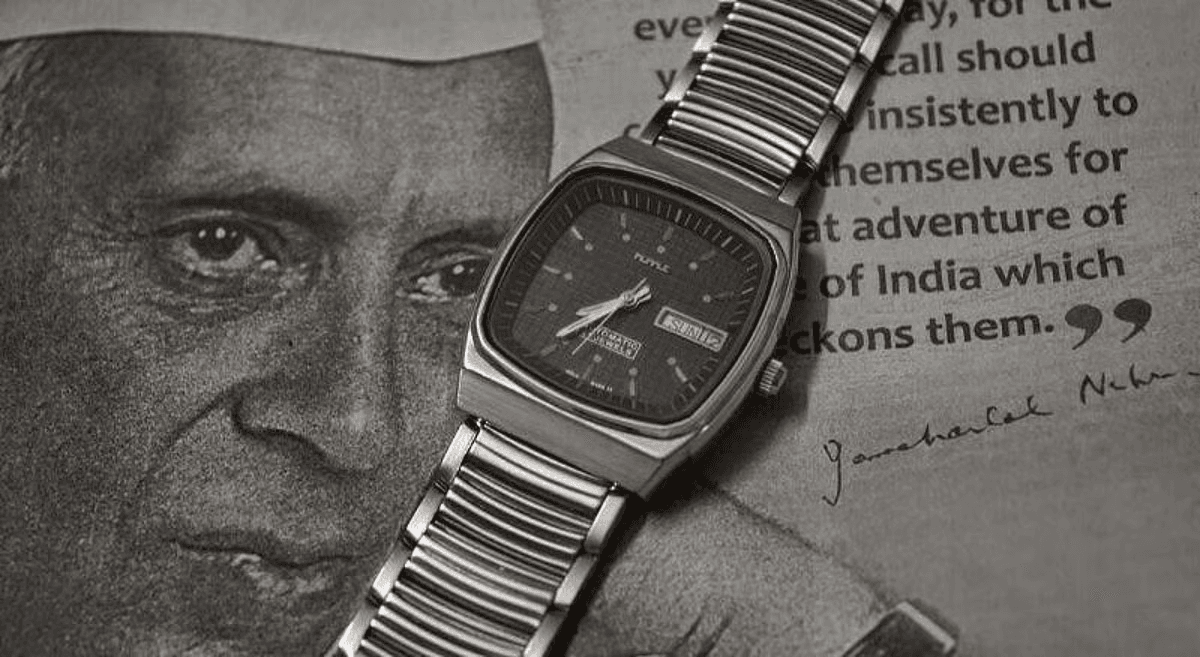

For decades, Hindustan Machine Tools or HMT was more than just a watch brand. Dubbed the “timekeeper of the nation,” its watches marked weddings, exam milestones, and everyday rituals across India. From heads of state to factory staff, slipping on an HMT was once a democratic symbol of progress. It was a product that transcended class and geography: affordable enough to be bought from a small-town showroom yet dignified enough to sit on the wrist of a prime minister.

But by the late 1980s and ’90s, the tide turned. Quartz technology arrived cheap and fast, Titan seized the design and marketing high ground, and HMT—burdened by bureaucratic inertia—fell behind. When liberalisation opened India’s doors to foreign imports, the brand’s mechanical charm was swamped. HMT was finally liquidated in 2016, leaving behind a nation’s worth of nostalgia and a swelling grey market of fakes.

That nostalgia never truly disappeared. In August 2024, Union Minister HD Kumaraswamy reignited hope by announcing a government committee to study HMT’s revival. The idea briefly stirred headlines—Kumaraswamy even bought vintage HMTs at a festival and presented one to his son—but momentum soon fizzled. The state’s attention shifted elsewhere, and the brand slid back into limbo. Into that vacuum stepped a group of watch lovers who also happen to be design professionals: NYUCT Design Labs, a Mumbai-based venture design collective.

Why HMT Still Matters

For Manojeet Bhujabal, a partner at NYUCT, the case for revival begins with memory but extends into hard business logic. “We all grew up with HMTs in our families. These watches have lasted 30–35 years and still tick. Quartz can’t match that kind of soul,” he says.

Nostalgia aside, Bhujabal points to a striking gap in the Indian market. Between entry-level quartz watches and luxury Swiss imports lies a barren space: the ₹10,000–₹25,000 bracket for accessible automatics. “Today, you won’t find a strong Indian automatic under that range. That vacuum is where HMT belongs.”

It’s a point that hits home when you consider the flood of fake HMTs online. ‘Frankenwatches’ stitched together from spare dials and donor movements are now common in collector groups and even turning up in influencer reels. The demand is real, if messy. “All you need to do is spread the message: are you wearing an original or a fake?” Bhujabal argues. “That one whisper can change how the market behaves.”

Globally, state-owned brands have walked similar roads. East German manufacturers splintered after reunification, with private revivals like Glashütte Original finding new life under the Swatch Group. Soviet stalwarts such as Raketa and Vostok survived only in private hands. Even in the West, Timex has thrived by reviving heritage designs at accessible prices. The message is clear: government-run models rarely endure, but private or hybrid structures can. Bhujabal and his colleagues aren’t insisting on state manufacturing; their flexible blueprint includes licensing, private partnerships, even crowdfunding if needed. The point is less about ownership and more about relevance—a national watch brand that means something in today’s India.

Reimagining A National Watch

That relevance, Bhujabal argues, requires both respect for heritage and willingness to reimagine. NYUCT’s speculative renders have already circulated online, showcasing modernised takes on the Janata and Pilot, updated with Devanagari numerals, textile-inspired straps, and commemorative editions such as a 1942 Quit India tribute. The intention isn’t just to tease collectors but to demonstrate possibilities: watches that speak India’s visual languages while keeping price points democratic.

“An HMT cannot afford to be exclusivist,” Bhujabal stresses, contrasting his approach with Titan’s Jalsa, a ₹40 lakh showpiece produced in just 10 pieces. “That might honour Indian craft, but it’s out of reach. HMT was in everyone’s hands—it transcended class. A revival has to recapture that accessibility.”

Accessibility, in Bhujabal’s view, doesn’t mean sameness. He sketches a layered portfolio: the Janata priced below ₹20,000, Pilots and Jawans in the ₹20,000–₹25,000 corridor, and special collector’s editions higher up the ladder. Collaborations with artisans, straps made from fruit leather for sustainability, dials inspired by India’s weaving traditions, or commemorative pieces linked to cricket and spaceflight—all of these, according to him, can give HMT modern relevance without losing its civic character.

Here, the global context matters again. In Germany, Junghans still sells minimal, affordable mechanicals with a design pedigree. In Russia, Raketa thrives as a heritage brand drawing on Cold War history. Even Casio—the company that once popularised quartz to HMT’s detriment—has recently launched its first mechanical Edifice. For Bhujabal, these examples prove that “timeless” doesn’t mean stuck in the past. “Design and style move in cycles. What was once dismissed as outdated can feel right again, if presented with honesty.”

Challenges remain, of course. Convincing the government to act is one; tackling the flood of fakes is another. But Bhujabal sees opportunity in both. Licensing alone could provide revenue for the state, while offering certified authenticity to customers. And the optics of a Prime Minister or defence officer wearing a revived HMT, he suggests, could do more for brand legitimacy than any marketing budget. “Politics is all about messaging,” he says. “If you’re serious about Make in India, why isn’t HMT on your wrist?”

For now, NYUCT’s work is speculative, but it has already sparked conversations among fans, collectors, and policymakers. Whether the road ahead runs through government committees, private investors, or grassroots crowdfunding, the bigger question is whether India still wants—and deserves—its national timekeeper back.