Bombay in the late 19th century fancied itself a city on the rise. Gaslights were giving way to electric chandeliers, carriages to the occasional motorcar. On Waudby Road, opposite the Gymkhana and with the Arabian Sea as a backdrop, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata commissioned a residence that was less home and more declaration of intent. Esplanade House, designed by British architect James Morris, combined classical symmetry with startling modernity: a marble staircase beneath a glass roof, a banquet hall glittering with chandeliers, even a private lift—an audacious novelty for Bombay in the 1880s.

When the house was complete, Tata’s thank-you to Morris came in the form of a custom Patek Philippe five-minute repeating chronograph in pink gold. The caseback was engraved with one simple line; “Presented by Jamsetjee N. Tata to James Morris, the architect of Esplanade House Bombay, 1890.” Both house and watch belonged to the same world: fusions of European technique and Indian ambition, built to outlast their owners.

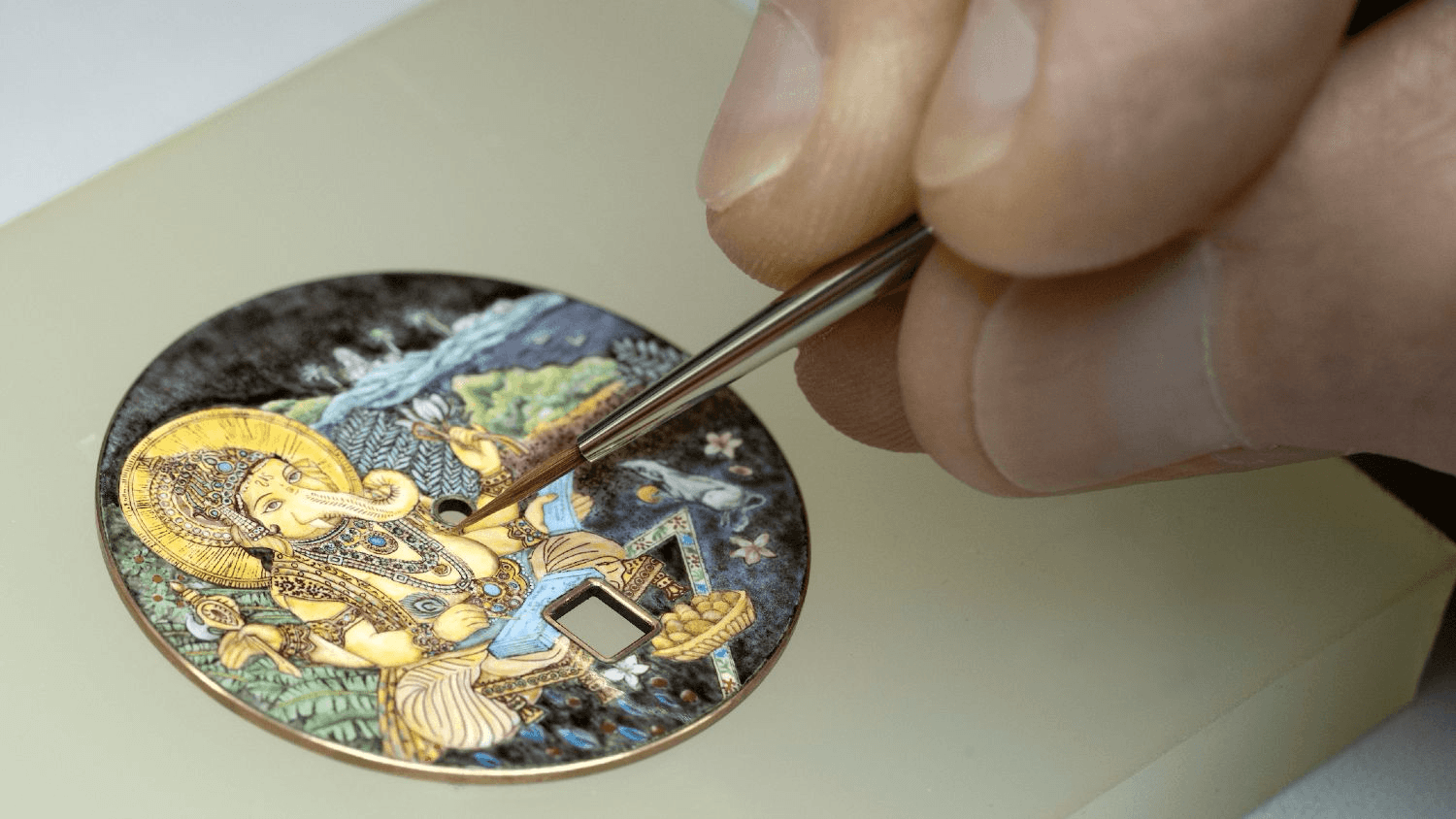

That act of gifting captured a wider truth about the time. Before global editions and commemorative dials, Swiss watchmaking in India was an affair of correspondence and personal persuasion. The Maharaja of Patiala commissioned gem-studded Cartier timepieces to match his commissioned jewellery from the maison. The Maharaja of Kutch, more technically minded, ordered a platinum Patek Philippe that would resurface generations later at auction. And not far from the courts, Jaeger-LeCoultre found its own muse in the polo fields of Jaipur, crafting custom Reversos for the Sawai Man Guards, their flip sides painted with regimental emblems, portraits of Maharanis, or even scenes of Krishna.

These weren’t limited editions in the modern sense, but they set the stage for what would follow: intimate collaborations that reflected a mutual fascination between Indian patrons and Swiss maisons. What began as personal relationships between ruler and watchmaker would, over the next century, evolve into a more structured form of flattery—the India Special Edition.

Modern Day Renditions

In 1997, as India marked its 50th year of independence, two Swiss maisons issued what many collectors now recognise as the first ‘official’ India specials. Cartier—a brand with a long history of bespoke jewellery among India’s elite—produced a Tank Américaine “India 1997”, limited to 50 pieces in yellow gold, with “India 1997” engraved on the back. Corum followed with the “India Golden Anniversary”, another 50-piece run with the Taj Mahal etched onto the dial and the words “Golden Anniversary, 1947–1997” on the caseback.

These weren’t bespoke commissions for maharajas or collectors; they were maison-issued, branded India editions, sold as symbols of national pride. In hindsight, they mark the kickstart of the modern India special edition concept — the moment Swiss watchmaking recognised India not only as a market, but as a story worth engraving into their own history books.

“India-specific limited editions began appearing in the late 1990s and early 2000s,” confirms Karan Vaidya, Chief Sales Officer of Rose The Watch Bar. “Cartier created a Tank to mark 50 years of India’s independence. Audemars Piguet produced the Royal Oak Offshore Sachin Tendulkar edition as well as a Royal Oak with Hindi numerals. Girard-Perregaux designed a special GMT that uniquely accounted for India’s half-hour offset. And Franck Muller released two limited editions—the Master Banker and Secret Hours—designed by my father to commemorate 60 years of independence.”

Released in the late 2000s, the Sachin edition became a poster child of sorts, both for its cricketing tie-in and for how it sold outside India. It proved that an “India watch” could escape its borders; even today, it commands just over Rs 23 Lakh on the reseller market—handsome numbers for a 300-piece limited edition AP. As Vaidya put it: “Globally, luxury has trended toward exclusivity — so simply having access to a limited edition adds to its desirability.”

Still, the real shift came a decade later, when Indian retailers stopped waiting for Geneva and began steering the process themselves. “To be candid, India-specific editions are a relatively recent trend, especially at the scale we are seeing now,” says Pratiek Kapoor of Kapoor Watch Co. “When I first joined the business, most limited editions were either global or regional, rarely tailored for India. But over the last decade, brands have started exploring India-focused models more seriously. One of the first ones was done by us in 2017 when we were celebrating our 50th anniversary & we had done a 50-piece limited edition again with Hublot. Post that Panerai, Breitling, Chopard, Franck Muller are a few brands I can name who have done India-specific limited editions.”

For Vaidya, this evolution reflects India’s new position on the global luxury map. “Earlier, brands relied heavily on diaspora clients. Today, India itself has become one of the fastest-growing luxury markets, and that local appetite has made brands pay closer attention to India-specific editions.” Kapoor frames it more bluntly: “In India, the phenomenon of aspirational buying exists and factors like Bollywood and cricket tie-ups can be powerful accelerators of demand, particularly among younger buyers and first-time luxury watch owners.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, behind every glossy launch lies a slow, bureaucratic process. Retailers float the idea, brands refine it, and approvals grind along at a characteristically Swiss pace. What looks like a commemorative quickie can take years and faces several hurdles that retailers need to conquer before a brand signs off.

“The idea usually originates either from a retailer or the brand’s regional or product team,” explains Vaidya. “It begins with a concept sketch, which must be approved internally by the brand’s design and product divisions. Retailers are then shown the draft to gauge interest and offer feedback. Once the design is finalised, it moves into production — a process that typically takes six months to a year.”

“It usually starts with a concept tied to a meaningful occasion like a brand anniversary, cultural milestone, or some kind of collaboration,” adds Kapoor. “We pitch the idea, theme, and quantity to the brand, and once aligned, move into design iterations which takes a while. After that come legal checks, approvals, and finally production. The full cycle can usually take up to anywhere between 12 to 36 months.”

This back-and-forth reveals a deeper truth: retailers are not just middlemen, they are cultural translators. As Vaidya puts it: “We reflect consumer sentiment and help brands understand whether the idea will resonate.” Kapoor agrees, though more bluntly: “The strong retailers like us do have an important role to play. While the final call always rests with the brand, we bring a lot of on-ground insights that help shape those decisions.”

Who the watches are for also matters. Kapoor is pragmatic: “It is mostly seasoned collectors and loyal clients who are after something exclusive. First-time buyers rarely start with a limited edition though occasionally a strong narrative that personally resonates or emotionally connects with them can become a purchasing factor.” Vaidya sketches the broader pool: “Seasoned collectors are naturally drawn to the rarity, but there’s also a segment of patriotic enthusiasts who may not buy watches often yet are moved by the Indian element.”

Beyond The Obvious

What, then, does a modern Indian edition actually look like? The answers, again, split. Vaidya champions subtlety: “The most successful editions are those that remain true to the brand’s design language while quietly weaving in Indian identity. The ‘Indian-ness’ should feel authentic, not ornamental.” He also adds a warning: “The worst outcome is when a model feels like a standard design painted in new colours — that’s not an edition, that’s a shortcut.” Meanwhile, Kapoor argues for boldness: “Yes, India is definitely carving out its own watch design language… A great example is the recent Bulgari Serpenti exhibition at Mumbai’s NMACC, where they brought in serpent-inspired art that really tapped into India’s deep cultural connection with the symbol.” For him, the bigger point is that “International brands are now seeing India not as an afterthought but as a market that deserves its own vocabulary.”

The debate mirrors India itself: part minimalist, part maximalist. And nowhere is this clearer than in the extremes. At one end are finely tuned editions with subtle cues. At the other, Jacob & Co’s full-throttle theatrics. Founder Jacob Arabo has staged a targeted assault on India’s HNIWs: a saffron-strapped Ram Mandir Epic X watch depicting Lord Ram and Hanuman, a ‘Sher-e-Punjab' variant referencing Sikh sentiments, and a Salman Khan dual-time special carrying Bollywood’s stamp of approval. Religion and celebrity, god and cinema—in Jacob’s playbook, both are levers for capturing India’s top-tier buyers.

It’s tempting to dismiss such watches as more flash than substance, but that misses the point. India’s special editions are no longer about commemoration alone; they have become instruments of signalling; about money, about taste, about belonging. In a country where a Rs 30 lakh watch can be bought as readily for faith as for fandom, subtlety is not always the currency. “With special editions, it’s less about resale value and more about collectability, storytelling, and emotional resonance,” echoes Kapoor.

And this, perhaps, is the future of Indian specials: a chessboard where brands, retailers, and collectors all make moves in different registers. Some play quietly, sliding peacock motifs into enamel dials. Others move loudly, strapping saffron leather to a gold case. Together, they chart a map of where India sits in global watch culture; ambitious, fragmented, and increasingly impossible to ignore. The chime of Tata’s repeater might have been an opening move. Today, the game is still unfolding, and the pieces on the board say as much about who has wealth as they do about who has taste.