Sazerac Company, the largest American distiller and owner of classic bourbon brands like Buffalo Trace, Weller, and Eagle Rare, is on a mission to raise the profile of American whiskey to the level of Scotch in India. India is the world’s largest brown spirit consumer, but sales of American whiskies (including Bourbon, Tennessee whisky, Rye whisky, etc.) currently constitute less than 1% of the market, far behind Indian, Scotch and Irish whiskies.

Sazerac has been strengthening its presence in India considerably in recent times, having acquired a 60% controlling stake in John Distilleries, the makers of the award-winning Single Malt Paul John and the popular blended Indian whisky Original Choice. And as part of an effort to familiarise Indians with the nuances of bourbon, the company recently flew down local whisky writers to the Buffalo Trace Distillery in Kentucky, the heart of American bourbon country, and Man’s World was on hand.

Driving into Frankfort, Kentucky, feels like entering a postcard: lush green fields, elegant stud farms, and picture-perfect barns stretch across the horizon. The Buffalo Trace Distillery sits tucked among these rolling pastures — 400 acres of history that only comes from doing something for over two centuries. Its history dates back to 1775, when Hancock Lee set up a small still along the Kentucky River. Since then, it has worn many names—O.F.C., George T. Stagg, and today, Buffalo Trace, under Sazerac ownership — and has survived fires, floods, Prohibition, and even a tornado, earning its title as the oldest continuously operating distillery in the United States.

From the outside, you can’t quite tell how large it really is — until you step in and realise that everything is alive and in motion. Nearly half a million visitors walk these grounds each year. As you enter from the parking lot to the visitor centre, the first thing that hits you isn’t sight or sound, but smell — warm, buttery, sweet corn steaming somewhere in the distance. It’s a smell familiar to most of us—the scent of bhutta carts. A whiff of fermentation follows — cornflakes, caramel, and freshly baked biscuits — the kind of scent you can’tbottle.

Right by the visitor centre stands Thunder, the iron buffalo, watching over the distillery like a silent guardian. [PS: Kentucky isn’t just Bourbon Country — it’s also home to some of the world’s most expensive Derby horses. The connection? That same limestone water. It nourishes both the grains that make great whiskey and the grass that feeds champion thoroughbreds.]

Bourbon was officially declared America’s native spirit in 1964. And for someone like me, who’s spent recent years fascinated by what makes one liquid more storied than another, there couldn’t have been a better time to visit this iconic distillery. But before we head inside the distillery, here’s a quick Bourbon 101 — because like all good stories, this one begins with the basics. A quick cheat sheet you’ll want to have before sipping.

- Think of Bourbon as a cousin in the global whisk(e)y family, with its own strict rulebook.

- It’s a type of whiskey (written with an ‘e’) and must be made in the U.S. (though not only in Kentucky).

- The mash bill—the recipe of grains—must contain at least 51% corn.

- It has to be aged in new, charred oak barrels (not necessarily American Oak)

- Distilled to no more than 160 proof, barreled at no more than 125 proof, and bottled at no less than 80 proof.

- Those charred oak casks are the secret sauce, giving bourbon its signature notes of vanilla, caramel, and a gentle sweetness that set it apart from Scotch’s smoky austerity or Japanese whisky’s subtle elegance.

Proof vs. ABV

The term goes back to the bootlegging days of the 1800s, when buyers wanted proof that their whiskey wasn’t watered down. To test it, they would mix the spirit with gunpowder and light it. If it sparked — it was ‘proof’ that there was enough alcohol. If it didn’t, you’d been duped. Thankfully, science has evolved since then. Today, proof means double the alcohol by volume (ABV) — so a 90-proof bourbon is 45% ABV, 100-proof is 50%, and so on.

Mash bill: The ‘recipe’ of whiskey

Think of the mash bill as a playlist, a lineup of grains that sets the tone for the entire performance. Corn is the headliner, but rye, wheat, and malted barley play their riffs in the background. Corn brings the sweetness, rye adds a touch of pepper and spice, wheat softens the mouthfeel, and malted barley adds structure and balance. When distillers say “high-rye” or ‘wheated’, it’s shorthand for flavour: the former is bold and spicy, the latter soft and rounded. Each distillery guards its mash bill like a family secret.

Bourbon vs Rye vs Tennessee Whiskey

- Rye whiskey: At least 51% rye grain, more pepper, bite, and dry spice.

- Tennessee whiskey: Legally the same as bourbon, but with one extra step—the Lincoln County Process, where the spirit is filtered through charcoal, smoothing out the edges.

Why Kentucky?

If you’re like me and wondering why 95% of bourbon is made in Kentucky, it’s a tale of geology as much as tradition. The midwestern American state sits on a massive limestone shelf that naturally filters out iron, while adding minerals like calcium and magnesium that help fermentation thrive. The region’s distinct four seasons — including blazing summers and cold winters — make the oak barrels expand and contract, infusing the spirit with layers of flavour from the new oak barrels in a way that cooler climates (like Scotland) simply can’t. Add abundant cornfields and easy river access for shipping barrels down the Mississippi to New Orleans, and you’ve got the perfect storm for Bourbon’s rise.

Behind the Barrels

The tours at the Buffalo Trace Distillery aren’t quick walkthroughs of an experience centre; they are built around the daily hustle and bustle. You see workers inspecting casks, checking fills, moving barrels — not for show, but because this is real production, seamlessly integrated into the visitor experience. As one of the guides quipped, “We run it every day — and it runs like a good old Chevy.”

Inside, thirty-two fermenters, each holding over 90,000 litres, bubble quietly in the fermentation room. The cask-filling and dumping stations operate like clockwork. Even in the bottling rooms, much of the process remains hands-on — a nod to the distillery’s ‘people over machines’ ethos. Every day, the team fills about 2,000 new oak barrels with the famous Alligator Char (#4), which gets its name from the cracked, reptilian texture on the inside of the stave. While it takes around 60 years to grow an oak tree, only 2 barrels can be made from one tree.

During my visit, I was lucky to witness a milestone moment: Buffalo Trace’s nine-millionth barrel. To celebrate, the team gathered around, signing the barrel before it was rolled into a special display room (Warehouse V) where it enjoys panoramic views of the distillery till the ten-millionth barrel replaces it — a literal crowning glory.

Buffalo Trace is one of the largest single-site bourbon distilleries in the world, building new warehouses every two months and filling them just as quickly. It’s also home to the world’s first bourbon archaeologist, Nick Laracuente, who leads fascinating tours tracing how early settlers distilled spirits on this very ground 200 years ago.

The distillery’s name itself is a nod to the past: the ‘trace’ was a path where buffalo once crossed the Kentucky River. That bend in the river — a natural shallow — gave the site both its name and its soul.

The Innovation Wing: Warehouse X

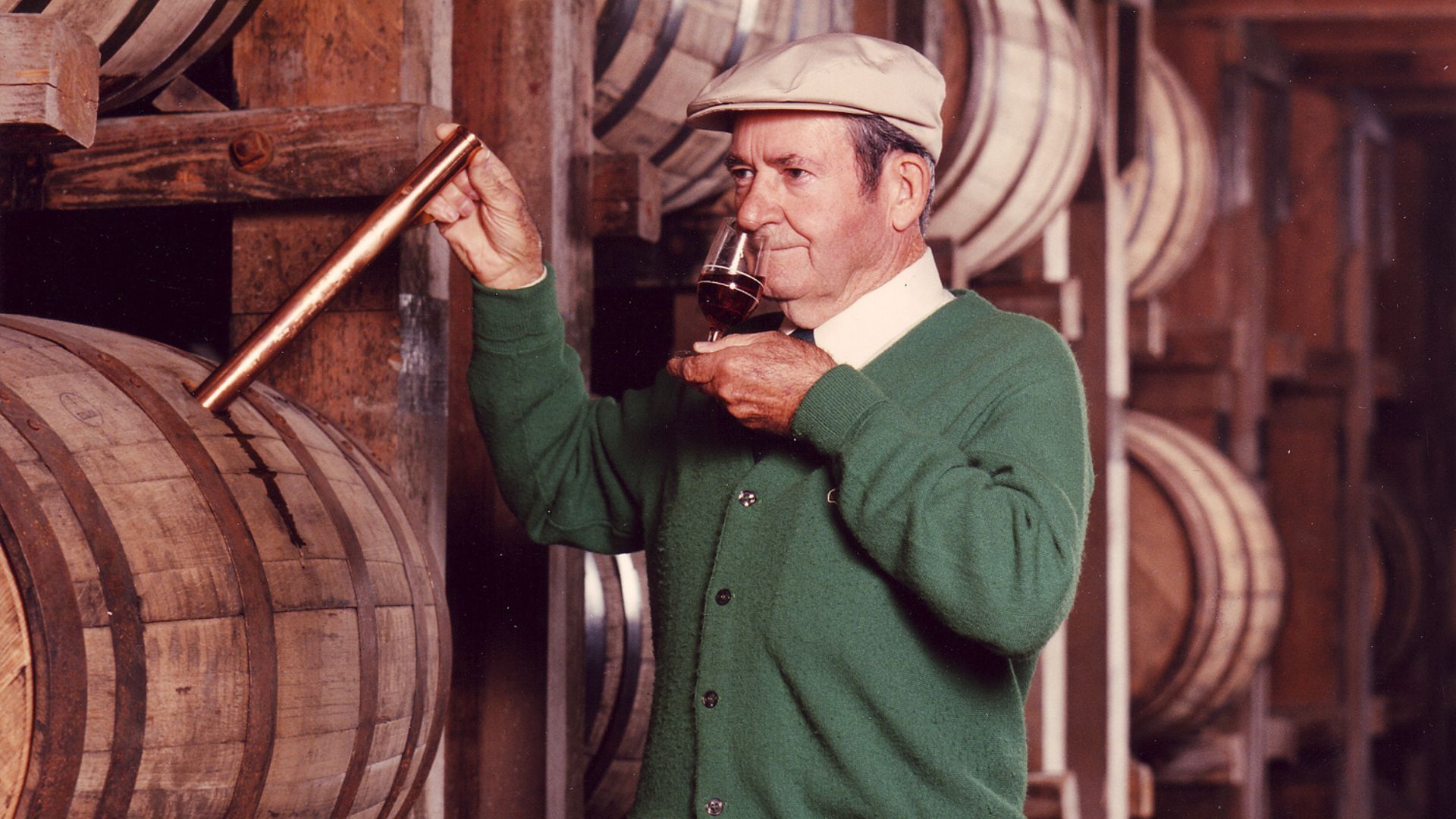

One of the highlights of the trip was an evening spent inside Warehouse X with Harlen Wheatley, Buffalo Trace’s Master Distiller and an industry legend. Warehouse X isn’t just a storage building; it’s an experiment in motion. Divided into five chambers — four climate-controlled and one left natural — it’s a 20-year-long research project testing how factors like temperature, airflow, and humidity influence whiskey maturation.

Inside, barrels are exposed to different conditions: one might be subjected to steady heat, another to fluctuating humidity, and a third to zero air circulation. “We’ve learned that temperature swings matter more than anything,” Harlen says. “Whiskey ages faster and deeper when it’s forced to adapt.” From this ongoing experiment comes the Experimental Collection, where small batches showcase the results of these tests—each a different data point in Bourbon’s evolution.

When I ask Harlen about the most surprising outcome, he laughs. “We once had a tornado rip through the distillery. The barrels exposed to the open air produced one of the best releases we ever made — the Tornado Surviving Bourbon.” He also points out that even subtle variations matter. “Move a barrel from the top floor to the bottom and you’ll taste the difference. The heat up top pulls out more spice and punch, while the lower floors add oak and caramel.” As he says, you can’t help but appreciate how bourbon is made — it’s nurtured.

The Single Oak Project and the Quest for Perfection

If Warehouse X is about science, the Single Oak Project is about the tree’s soul. Here, the distillery is literally tracking Bourbon’s journey from tree to glass and every variable — where the oak tree came from, which part of the tree was used, and how many growth rings it had. Considering it takes approximately 60 years to grow one oak tree, and only two barrels can be made from it, that’s a staggering level of detail.

The goal? To find the perfect bourbon. (For the record, they still don’t believe they’ve made it yet.) And Harlen adds, “But every experiment takes us one step closer.”

That pursuit of perfection — while celebrating the imperfection and difference along the way — is what makes Buffalo Trace interesting. After all, whiskey, like people, reflects its environment.

Four Mash Bills, Endless Expressions

What’s fascinating is how the same mash bill can yield completely different expressions just by age or warehouse location. For instance, Benchmark (aged ~4 years, 80 proof) feels young and nutty, while the same mash bill aged 7–8 years becomes Buffalo Trace (90 proof)—smooth, balanced, with a hint of vanilla sweetness. Keep it longer at the lower rickhouselevels (the position within a maturation warehouse), and you get Eagle Rare 10—rich with caramel, butterscotch, and Christmas cake warmth. The key lies in how each recipe interacts with time, proof, and place.

A bourbon must age at least two years to be called ‘straight bourbon’, but most Buffalo Trace spirits rest much longer. To put it in context, a 10-year-old bourbon is roughly as mature in flavour as a 16–18-year-old Scotch. Kentucky’s climate works faster. When you remember that everything here begins as a clear spirit —'white dog’ — and only becomes amber and complex after years of resting in oak, it’s hard not to marvel at what time can do.

- Mash Bill #1 (Corn, Rye, Barley): Used for Benchmark, Buffalo Trace, Eagle Rare — the sweet spot mash bill.

- Mash Bill #2: Higher rye for a spicier profile.

- Mash Bill #3: The wheated mashbill – where Wheat replaces rye — think Weller and Pappy Van Winkle.

- Mash Bill #4: The rye mashbill – a little bolder and aromatic.

So, if you love the elusive Pappy Van Winkle but can’t find it (who can?), reach for Weller — it’s also a wheated mash bill and boasts some impressive age statements, like Weller 12 which was released in India last year. As Harlen explains, “Until it reaches the warehouse, bourbon is science. Once it's inside, art takes over.”

Today, bourbon’s influence stretches far beyond Kentucky. With Sazerac’s investment in Paul John Distilleries, Buffalo Trace, Benchmark, Sazerac Rye, and Weller are now available in Mumbai, Bangalore, and soon Delhi NCR. According to the What India Is Drinking Report (2024), bourbon’s share in India’s premium whiskey segment has doubled since 2022 — proof that the category is quietly finding its footing in Indian bars and homes. What makes this especially smart is how Buffalo Trace balances accessibility with aspiration — from entry-level bottles like Benchmark to rare collectors’ editions, it gives consumers choice without compromise.

By the time I left the distillery, the sun was setting over the Kentucky River, casting a golden glow over rows of rickhouses. The air smelled faintly of charred oak and vanilla, along with the laughter of a nearby tour group. They live by the motto: Honour Tradition, Embrace Change. And you can see that philosophy in every detail.