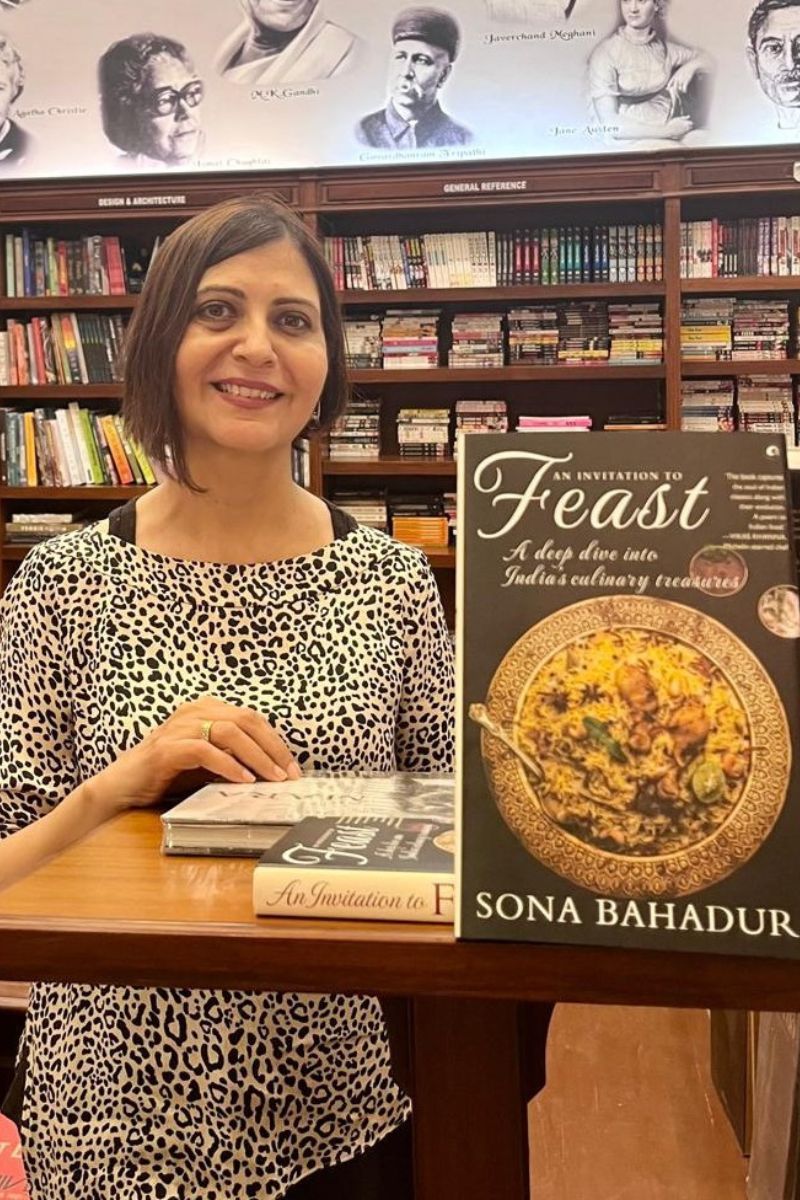

Sona Bahadur, who achieved fame a decade ago when she transformed the BBC Good Food magazine’s local edition into the finest culinary magazine in the country, journeyed through the length and breadth of India to report for this book. Its genius lies in the simplicity of both the subjects and their treatment. The author explores interesting stories behind 11 common dishes that most Indians are familiar with--Butter Chicken, Dosai, Chhole, Goan Fish Curry, Undhiya, Biryani, Dhansak, Shami Kebab, Vada Pav, Smoked Pork and Rasgulla. And in the treatment, she transforms these everyday fares into glorious delicacies by taking us to the city that it is most associated with, and into the kitchens of the people and restaurants who have spent long years perfecting the dish and their variations. For the best Chhole experience, for example, she takes us to homes and restaurants in Amritsar, for Shami Kebabs naturally to Lucknow, for Undhiya to Surat, Ahmedabad and Mumbai, for smoked pork to Guwahati, Dimapur, Shillong, the villages of Meghalaya, and Mumbai, and for Biryani to Lucknow, Rampur, Hyderabad, Chennai, Kolkata and Calicut.

An Invitation to Feast is a masterclass in food writing, up there with the best of culinary journalism in India. Bahadur’s only failing is that she didn't have a videographer tailing her prandial perambulations. Or she would have also been an Instagram celebrity by now.

Here’s an excerpt from the section where she travels to Calicut to explore its famous Thalassery Biriyani.

Thalassery Mutton Biriyani with Faiza and Chovakaran Moosa

North Kerala’s Thalassery biriyani is a kind of Malabar-and-Middle East union that reflects the region’s Arab influence.

To me, everything about the Mappila Muslim biriyani is exceptional. The short-grain kaima rice sourced from hilly Wayanad, the unique eight-spice Mappila masala blend, the garnish of jewel-like golden raisins, and the one-of-a-kind accompaniments. It’s even spelt differently—biriyani, and not biryani.

In my opinion, no one makes it better than Faiza Moosa, the author of Classic Malabar Recipes. For over three decades, Faiza and her husband Chovakaran Moosa have crisscrossed the globe, spreading the gospel of Mappila cuisine to places as far-flung as Lyon and New York. I first met the Moosas at Ayisha Manzil, their imposing, colonial-style Thalassery bungalow. Perched dramatically on a cliff, it offered the most dazzlingly cinematic view of the Arabian Sea. Faiza had produced a succession of extraordinary Mappila dishes—a meat porridge called alisa, tart tamarind prawns, and golden lakottaappams, or crêpes wrapped around sweet egg-coconut filling. It was the start of an enduring fascination with Malabari food.

The couple has since moved to Calicut due to Moosa’s failing health. When I connected with him about my biryani odyssey, he promptly invited me to fly down for a meal.

The day I did, it was raining on a Biblical scale in Calicut. The septuagenarian picked me up from my hotel in his bright orange Mini Cooper. ‘It’s the late-October rain of Calicut. We call it thula,’ he said, clearly enjoying the downpour, as we drove down to their characterful 200-year-old Calicut home.

Welcoming me to her kitchen with her trademark warmth, a shy, sari-clad Faiza demonstrated the path to a perfect Mappila biriyani. Dreamy layers of kaima rice and mutton curry were infused with sprinklings of rose water and saffron, slathered with garam masala and fried onions, studded with raisins and cashews, and slow-cooked. The layered loveliness was served with a date pickle, raita, papadums, and a zesty chutney of curry leaves, mint, coriander, and lemon.

As biryanis go, the taste was very subtle, which I found interesting, given that spices run riot in Kerala. Faiza attributed the nuanced flavour to her Mappila garam masala, a perfectly balanced mix of cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, caraway seeds, nutmeg, mace, and the defining spice of Mappila cuisine, aniseed.

We passed a convivial hour at the table. Liberated from his diet for the afternoon, Mr Moosa was determined to extract the last ounce of pleasure from his cheat day. ‘Tomorrow, Faiza and I complete forty-five years of marriage. We are putting today’s biriyani on my celebration account,’ he trilled.

An old hand at entertaining, he held forth on the central role played by biriyani at a Mappila wedding. The wedding feast includes three dishes: muttamala or egg garlands, alisa, and mutton biriyani. ‘We call it MAB,’ he said in his lilting Malayali accent.

Their wedding in 1979 was among the last to host the traditional Mappila supra—the traditional communal spread—before table service became the norm. ‘Everyone ate from a common platter. It was amazing,’ he said. Faiza had less happy memories from the event. Her two favourite goats were butchered for the wedding feast. ‘I was so sad that I didn’t eat anything,’ she said.

After lunch, we descended into the living room, where the couple showed me photos from their wedding album. Faiza, then a twenty something with henna-dyed palms, made a gorgeous bride. Not to be outdone, Moosa looked debonair in Aviators and a fine three-piece suit. ‘Wait, you wore sunglasses at your wedding, Mr Moosa?’ I ribbed. ‘Don’t blame me. It was the fashion that time,’ he said with an eye-roll.

As I prepared to leave, one gastronomic oddity about the Thalassery biriyani was still boggling my mind. While eating lunch, I had noted that the mutton masala was served separately from the biriyani, in a different bowl.

‘Oh that. That’s how we like it here,’ Moosa said. ‘The meat is cooked, then combined with rice, then separated again. Just like first you’re single, then you get married, and then you separate.’ The analogy evoked the most withering of looks from the wife. ‘Not the best story to tell on the eve of your anniversary, Mr Moosa,’ I teased. Moosa looked uneasy. Faiza blushed furiously.

It was an adorable moment. The love story of meat and rice might not always end happily ever after, but the Moosas are undoubtedly a match made in heaven.

Fish Biriyani with Abida Rasheed

The Mappila meen (fish) biriyani has a certain je ne sais quoi that sets it apart from its mutton counterpart. I couldn’t imagine leaving Calicut without a taste and dropped in at YouTuber and food consultant Abida Rasheed’s home in the sylvan suburb of Calicut’s Vengeri.

‘Meeeen biriyani has to be a meeeal by itself. Nothing should interfere with it,’ she said emphatically. ‘You need to smell it, touch it, feel it. All your senses should hunger for it. Now that’s what I call a fish biriyani,’ she gushed in her lyrical, full-throated voice. ‘And I’m going to eat that today,’ I said, grinning. ‘Inshallah!’ said she. ‘By God’s grace you shall.’

The tradition of making seafood biriyani is unique to north Kerala. Living in the midst of such marine abundance, it’s not surprising that the Malabaris take full advantage of this plenitude. The Arab influence might be at play, too. ‘A lot of Yemenis, known to combine rice with fish, came to the Malabar as traders and influenced our cuisine,’ Abida pondered.

Though associated with the region, Abida pointed out, fish biriyani isn’t a common dish in these parts. ‘Only certain upper-class families make it. The common man cannot afford to buy seer fish. And since fish breaks easily, this biriyani is more suited to parties than weddings.’

The recipe she recreated for me dated back generations. Reflecting on the flavourful dish of her grandmother, Abida recounted the care with which she would make fish biriyani. ‘Meen biriyani was like a festival in our house. My grandmother would make the spice powder herself using produce from our own plantations. Because Mappila women didn’t go out of the home during those days, she would instruct my dad or grandfather on which fish to buy. After the fish was bought, she would complain it had not been cut properly. The drama would just go on and on,’ she said, smiling at the memory.

Watching Abida cook, I noted that the key differentiator in her fish biriyani was a wet masala made from coriander leaves, onions, ginger-garlic, and green chillies. Darne-cut pieces of seer fish were marinated with this thick paste before being shallow-fried. The fish was layered with cooked kaima rice, seasoned with Mappila garam masala, and left to cook on dum.

Even before we sat down to eat, I could sense this was unlike any other biryani I had eaten before. It smelled tantalizingly exotic, carrying with it the faintest whiff of the sea. The taste was extraordinary. The kaima rice, having perfectly absorbed the taste of the fish and masala, hummed with a piscine soulfulness. It was hard to imagine fish and rice could marry so perfectly.

I ate ravenously. ‘How come Thalassery biriyani isn’t more famous?’ I asked, genuinely astonished that something so fabulous had not been cemented on the culinary map. Abida blamed the under-promotion of the Malabar by the tourism ministry.

She also attributed it to ethnicity. ‘Us Mappilas are a matrilineal society. The brides stay back in their family. It’s the grooms who leave their homes to stay with their wives. So our recipes have remained in the homes.’

But she didn’t seem to mind too much. ‘We don’t really want too many tourists around here. We want to keep this part of the country to ourselves,’ she confessed, flashing me a mischievous smile.

Reproduced with permission from Aleph Book Company