The first time I tried the old wrestler’s bridge press from Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise, I felt my neck tighten before the barbell even left the ground. It was late evening at a Mumbai gym, fluorescent lights flickering, techno music bleeding out of someone’s AirPods. I planted my feet, pushed my shoulders back, and tilted until only the soles of my feet and the back of my skull were touching the mat. The weight hovered above my chest. No bench. No machine. Just gravity, breath, and a few confused double takes from the guy doing cable flyes nearby.

It was a ridiculous thing to attempt for someone who once woke up in 2022 unable to turn his head. But the book had insisted that “you can easily find time for a little exercise, which is no less important than any other dire necessity of life,” and I wanted to see what that century-old certainty felt like.

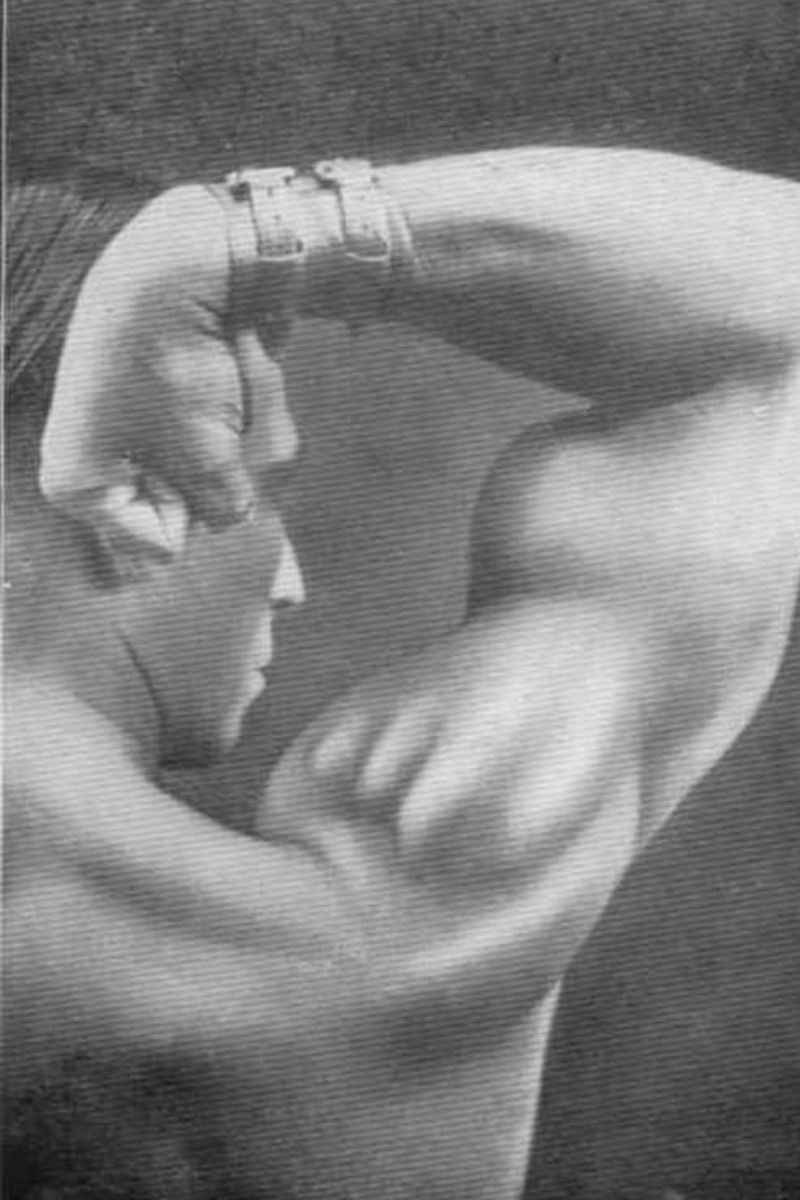

The movement was slow and unforgiving. I could sense how easy it was to overdo it, to lose the balance between control and collapse. Each rep demanded patience, not just power. I stopped counting halfway through and focused on breathing evenly, keeping the strain where it belonged. When I finally racked the bar, my head throbbed, my neck buzzed, and for a moment I understood what the author meant when he wrote that the goal of exercise was not display but “the power of application of strength.”

No mirrors. No metrics. Just a quiet awareness that strength, before it became something we performed for others, was something we learned to live with.

The Lost Language of Control

I found Muscle Control and Barbell Exercise late one night while scrolling through forgotten corners of the internet. Dating back to the early 20th century, it looked nothing like a modern fitness guide. No colour photography, no celebrity endorsements, not even proper exercise names. Just pages of grainy illustrations and dense text, written in the tone of someone who believed that discipline was the salvation of the modern young man.

Its author, Bishnu Charan Ghosh, was a legend of early Indian physical culture, and his preface reads like a sermon disguised as a training plan. “When you find time to sleep, to take your bath, to take your meals,” he wrote, “you can easily find time for a little exercise, which is no less important than any other dire necessity of life.” Exercise, to him, wasn’t a lifestyle choice; it was a moral obligation.

What many forget is that Ghosh started as a frail, undernourished teenager who could barely sleep. Under the guidance of Professor R.N. Thakurta, he rebuilt himself in three months. He later wrote that if one weak boy could change his body through discipline, then anyone could. It wasn’t elitist fitness; it was India’s first democratic wellness movement.

He called his manual a “humble attempt” to help others and promised that if a “single rickety boy” benefited from it, he would consider himself rewarded. In an era where every fitness account begins with “my transformation,” Ghosh’s goal was everyone else’s. He wrote as though the body were a classroom and everyone deserved to pass.

The exercises themselves are crude but elegant. Every movement is a compound lift. Every instruction reads like a negotiation between body and mind. There are no shortcuts, no apps, no talk of calorie deficits or macronutrients. You memorise the steps, fail, adjust, and try again. It is oddly freeing. Without machines or metrics, the only thing guiding you is your own awareness.

After a few weeks of practice, I realised what Ghosh meant when he said that muscle control “increases the power of application of strength.” It isn’t about being stronger than others; it is about learning how strength feels when you stop outsourcing it to equipment. Each rep asks for precision, not aggression. Each mistake teaches you more than a mirror ever could.

That sense of mindfulness, of knowing the body as an instrument rather than a project, reminded me of another Calcutta export: the samity.

Strength as Character

If Ghosh and his contemporaries were the Platos and Aristotles of Indian physical culture, the samitys were its academies. In the early twentieth century, they appeared across Bengal: small gymnasiums that doubled as community centres and, sometimes, covert revolutionary cells. Hatkhola Byayam Samity, founded in 1910, was among the earliest. Its members trained with maces and clubs in a narrow, oil-slicked akhara, then slipped out at night to deliver messages for the Anushilan Samity.

Their ethos was as practical as it was patriotic. The same discipline that forged stronger bodies could forge a stronger nation. When Swami Vivekananda urged young Indians to build “muscles of iron and nerves of steel,” he wasn’t talking about vanity. He was talking about moral capacity—the idea that to serve others, one had to be capable, resilient, awake… and perhaps, able to perform an upper-body split twice a week.

That spirit didn’t fade with independence. Hatkhola still trains over five thousand members today. Its regulars call themselves byambirs, not gym-goers. The air smells of oil and iron; portraits of Hanuman, Vivekananda and Sister Nivedita hang above the mud pits; and no one bothers with supplements or steroids. Some men there still train with donkaaths and mugurs, heavy wooden clubs passed through generations. Many younger members now alternate those with free weights, but the ethos hasn’t changed. Strength is still a form of character, not content.

When I spoke with Aviroop Gupta, who grew up training at Simla Byayam Samity before moving to Australia, he described the place as a “gloomy room full of cast-iron weights and arguments about politics.” His grandfather had been an Olympic hopeful in 1928; his father played league football. Exercise, in his family, was a kind of inheritance—a civic duty more than a lifestyle. In his youth, Aviroop also trained under Monotosh Roy, India’s first Mr Universe and a student of Ghosh’s, who kept handwritten notebooks tracking each student’s progress.

Roy became a national symbol in 1951, when he won the Mr Universe title in London as the first Asian to do so. Known for his balance rather than bulk, he taught that patience and proportion mattered more than power. His approach was slow, corrective, and almost yogic in its rhythm, fusing muscle control with meditation.

That image stayed with me: men resting between reps, debating ideas. In my own gym, silence rules. Everyone’s cocooned in headphones, tracking their sets through screens. The only conversation you are likely to have is over who’s next for the bench.

It’s tempting to romanticise the samity, but what fascinates me isn’t nostalgia; it’s continuity. Both Ghosh’s manual and those gymnasiums were born from the same impulse: the belief that strength, rightly cultivated, could shape something larger than the self. A man who could control his body could control his destiny. A nation that mastered discipline could master freedom.

Machines and Mirrors

I have spent the better part of a decade inside gyms—the modern kind filled with mirrors, LED panels, and chrome machines that look like props from a low-budget sci-fi film. They all promise the same thing: isolation. You isolate your triceps, your lats, your abs, your glutes. Every corner has a device designed to separate one muscle group from the others. If Ghosh’s world was built on integration, ours is built on dissection—and the isolation isn’t just in terms of muscle groups either, but socially as well.

At first, I loved it. Like most men in their twenties, I mistook exhaustion for progress and sneered at community-based fitness. I liked the rhythm of it, the count, the noise, the faint pride of watching definition appear where there used to be softness. But it wasn’t sustainable. Small injuries became chronic ones. My neck and wrists, in particular, turned traitor. One morning in 2022, I woke up and couldn’t turn my head without pain. I spent the week red-eyed and wincing, and faced the same kind of immobility in my hands after a few rushed CrossFit sessions gone wrong in 2023–24.

That was when I started to question what all this effort was for. What was I trying to build, exactly? A body that looked strong or one that felt alive? I had spent years perfecting form, learning to eat “clean,” and tracking progress down to decimals, yet most days I felt broken and insecure. I eventually switched to swimming with a close friend—something I did for years as a child. It wasn’t a revelation, just an act of necessity. The water was the only place my body didn’t complain. I stopped caring about hypertrophy and started caring about sleep and eating heartily after an hour of laps. The vanity of my twenties gave way to maintenance. Fitness, once about transformation, became about survival.

But something of Ghosh’s spirit stayed with me. His belief that movement could repair more than muscles, that it could reorder the mind, made sense in a way it never did when I was chasing symmetry. What the samitys called byayam wasn’t just exercise; it was an act of centring. When I swam, I could feel a faint trace of that same order: repetition as ritual, motion as meditation.

The Body as Ritual

The difference, of course, is that today’s rituals are private. We no longer train as communities; we train as algorithms. My gym, like most, is full of people chasing different goals in perfect silence. You can go a whole year without speaking to anyone. The closest thing to collective motivation is a shared mirror.

It’s strange to think how a practice once born in oil-lit akharas filled with slogans and songs has become a quiet room full of glowing screens. There’s something almost tragic in that solitude. Modern fitness promises empowerment, but often it just magnifies loneliness. We train to look confident but rarely to feel connected. The rituals survive, stripped of their context—the warm-up stretches, the protein shake, the post-set selfie—but they no longer form a story. They’re fragments of an identity we’re constantly updating.

Sometimes I wonder if Ghosh would even recognise this world. Would he see discipline or performance? Would he consider our sculpted backs and shredded abs the same kind of strength he spoke about? Probably not. His “power of application of strength” was about agency—the ability to act in the world, to repair what’s broken, to help someone else. Ours, too often, stops at the surface.

And yet, despite the noise and narcissism, I don’t think we’ve lost his vision entirely. We just express it differently. Every person who shows up to the gym despite exhaustion, who runs to quiet the mind, who learns to move again after injury, is speaking, in their own way, the same old language of control.

Maybe the urge to rediscover the old ways isn’t new at all. Around the same time Ghosh was teaching Calcutta’s youth to master their muscles, a German performer named Joseph Pilates was trapped in an internment camp on the Isle of Man. Watching his fellow prisoners grow weak, he began designing exercises using bodyweight and modified hospital beds. Out of that confinement came “contrology,” what we now call Pilates.

A century later, we still practise both men’s philosophies, sometimes without even realising it. Every yoga class, every Pilates reformer, every strength circuit that borrows from “functional” training is part of that same lineage.

Maybe that’s the quiet thread running through every act of exercise. Whether in a samity, a bodybuilding hall, or a modern gym, we’re all testing how much freedom can exist inside discipline. The body bends, trembles, heals. We repeat, we return. And somewhere between the repetition and the release, we rediscover a small, defiant kind of peace.